Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

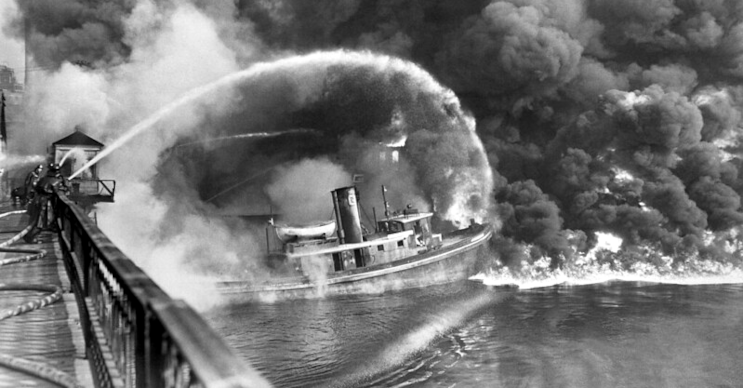

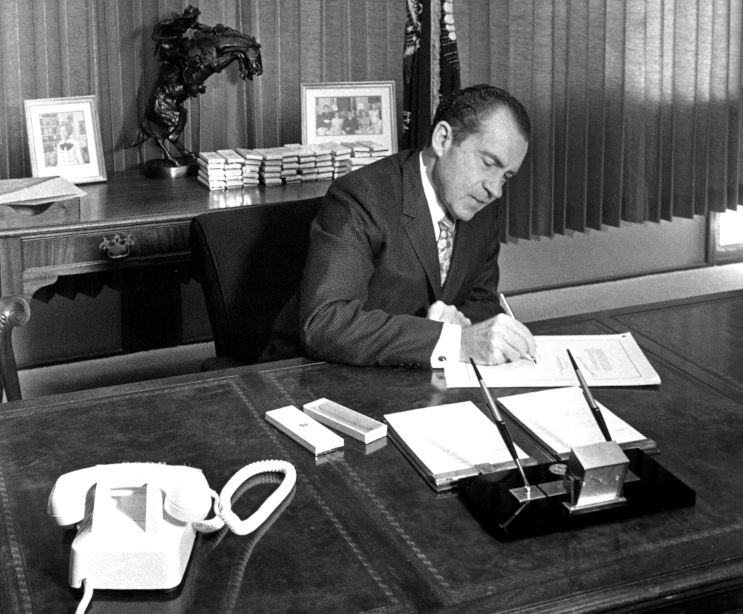

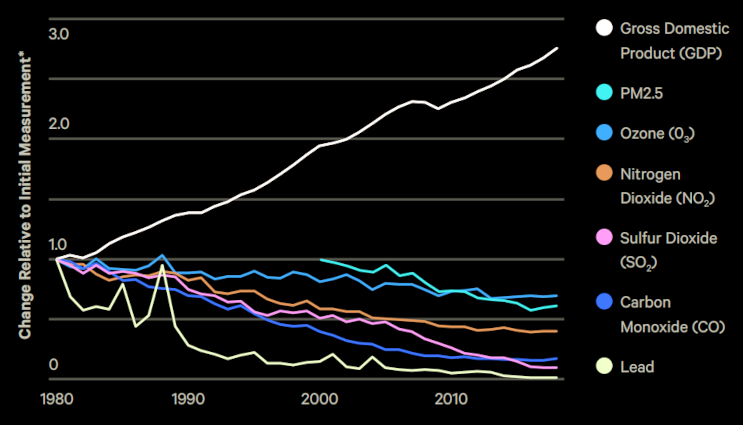

Image credit: Shane Burkhardt / CC BY-NC 2.0 1774 words / 7-minute read Summary: Recent years have seen the 50th anniversary of landmark U.S. environmental policies that achieved tremendous success in pollution reduction and natural conservation. As the awareness of artificial light at night as a significant source of environmental pollution rises, we examine whether a similar federal regulatory approach could meaningfully reduce light pollution in the United States. Light pollution is a serious environmental problem, but we have effective technical solutions in hand. Where the political will exists to confront the problem, public policy enshrines the decision and brings consequences if the law is not followed. In the United States, policies governing the use of outdoor lighting are usually made at the local level. With tens of thousands of such local governments, achieving change in the U.S. has been slow. But environmental history offers an alternative approach that could produce meaningful results. We call this effort the "Clean Night Skies Act". Is it a realistic option? A moment 50 years in the making2019-2023 saw the 50th anniversary of several landmark U.S. environmental policies. These include the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act. The period from the mid-1960's to the early 1970's marked a major shift in the way the U.S. manages pollution control and natural conservation. Before that time, the few environmental policies existed. There was not yet a broad understanding of the potential for human activities to harm the environment. But it was becoming clear that those activities were often harmful to both people and wildlife. The pace of environmental change accelerated after the Second World War. Pollution from heavy industry fouled the air over U.S. cities and poisoned its waterways. In 1962, the American conservationist Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, a book now considered a classic of environmental literature. Focusing on the effects of the indiscriminate use of chemical pesticides, Silent Spring was a clarion call. Many regard its publication as the start of the modern environmental movement. In considering the problems that Carson described, it became evident that many of the underlying problems are cross-boundary. That is, they don't respect jurisdictional boundaries. Air and water pollution drift from the places they are emitted into other regions. Endangered species can roam across large territories. Earlier attempts to control pollution and promote conservation at more local levels thus failed, and environmental quality in many places in the U.S. was poor by the mid-1960s. This was the result of rapid economic expansion, population growth, industrialization and urbanization in the century since the Civil War. Firemen stand on a bridge over the Cuyahoga River to spray water on the tug Arizona, as a fire, started in an oil slick on the river, sweeps the docks at the Great Lakes Towing Company site in Cleveland, Ohio, on 1 November 1952. (Public domain) Public attention to the problem rose during the second half of the 1960s. Two environmental disasters in 1969 were turning points in the story: the Santa Barbara oil spill in January-February and the fire on the Cuyahoga River in June 1969. Life magazine documented the latter with a photo spread in its August 1 issue, and Americans were horrified by what they saw. Faced with rising public alarm, Congress took action. Investigations showed decades of federal mismanagement of America's environment and natural resources. The problem and its proximate causes were clear, and the public demanded significant change. In the span of only four years, Congress created all the major pieces of modern federal environmental policy. Those laws were spectacularly successful. Emissions of air pollutants in the U.S. have dropped almost 80% since 1970. About 99% of all creatures listed under the Endangered Species Act have avoided extinction. If efforts to address these problems were undertaken only at the local level, it's unlikely these incredible results could have been obtained. And some states have enacted their own stronger or more restrictive policies governing environmental issues within their boundaries. From idea to lawThe U.S. federal government makes and implements environmental policy through a distinct process. Congress investigates issues and sets high-level goals and requirements in legislation. These acts establish new agencies to write regulations flowing from the goals of the legislation, or task an existing agency with the job. Agencies then write regulations through the federal rulemaking process, which includes public input. Enforcement actions are brought either within the agencies or through the federal courts. Courts may overturn regulations or acts of Congress in part or in whole. Congress may revisit environmental legislation and amend it if things aren't working well. And even when environmental policies become law, it usually takes the efforts of outside intervenors to ensure that the government enforces the laws as it should. How might this approach work if applied to reduce light pollution? First, Congress would take up the matter by putting its on its legislative agenda. Interested members of Congress may direct their staff to collect information on the topic. It may hold hearings on the subject, and some Members may state their willingness to sponsor legislation. Either chamber, or both, could consider simple resolutions to the effect that it is the sense of the chamber that the issue is important. Up to this point, the political risk associated with participation is low. If Congress moves toward writing new legislation, the stakes suddenly become higher. Depending on the exact content of a bill, legislators may be more or less willing to support the effort. It can take many years or even decades to achieve the consensus in Congress required to move major legislation. Once the consensus emerges, the rest of the process can move with lightning speed. U.S. President Richard M. Nixon signs the National Environmental Policy Act into law at the White House on 1 January 1970. (Photo courtesy of the Nixon Presidential Library) Promise and challengeThe Clean Night Skies Act is patterned on the environmental bills of the 60's and 70's. The text of the bill itself need not be lengthy or complex. It finds that, under some circumstances, artificial light at night (ALAN) is a harmful environmental pollutant and makes light pollution reduction a priority for the country. It then tasks the Environmental Protection Agency with writing regulations aimed at reducing its influence. As with other environmental pollutants, the EPA would determine "safe exposure" thresholds to ALAN. It would direct states and municipalities to come up with their own plans and policies to achieve light emissions standards. And just like in the Clean Air and Water Acts, it would fine jurisdictions that failed to hit the targets. A lot of factors favor taking this kind of approach. There is a scientific consensus on the significance of the problem. We're not waiting for a technical solution to that problem — we know what works. The solution involves merely reducing wasted outdoor light at night, which has no obvious downside. And better outdoor lighting that reduces light pollution has the extra effect of improving nighttime visibility, which in turn enhances public safety. But there is a lot that must happen first before we can get there. Light pollution really isn't on the federal policy agenda right now. Only some states have confronted the issue with legislation, but more seem interested every year. A Clean Night Skies Act starts with building a coalition of supporters in Congress. We must articulate a rationale for policy change (we're working on that). We have to educate Congressional staff about light pollution and ensure continuity across election cycles to keep the issue on their radar. It's true that the Clean Night Skies Act faces significant headwinds right now. The American electorate is bitterly divided over almost every issue. Light pollution is often framed as an "environmental" issue, making it an instant turn-off for some voters. We have to overcome complacency and political malaise that prevents the country from dealing with its problems. The American public perceives that outdoor ALAN is cheap to consume and has no downsides to its use; plus, people are afraid of the dark. Congress is in a state of near-total paralysis, enacting fewer than one percent of introduced bills this term. And there is some concern that light pollution as an environmental concern could be swept aside by attention to climate change. In the meantime...More importantly, light pollution hasn't yet had a "river on fire" moment that tips the balance toward a definitive solution. It is still acceptable in our society, given that its manifestations are often unseen by most people. Of those who know about light pollution, many associate it with astronomy and conclude that it's not a problem for them. As the world continues to brighten, we risk this "window of acceptability" both shifting and widening. In the meantime, there are alternatives. We could invoke existing environmental laws and argue before courts that they do (or at least should) apply to light pollution. But there are difficulties with this. In 2010 a group of light pollution activists sued the EPA, which had resisted calls to regulate light pollution under the terms of the Clean Air Act. The court sided with the government, finding that the Act's definition of "air pollutant" did not include ALAN. The message to the petitioners was, in short: if you want Congress to regulate light pollution, you must ask it to do so in the form of either new legislation or an amendment to the Clean Air Act. Although some other argument might carry the day, it seems that courts are unlikely to rule differently in the future. Another stopgap option is to convince a presidential administration to take action by executive order. As the Biden Administration took office, DarkSky International urged the President to issue an executive order regulating outdoor lighting on federal property. So far the Administration has not responded to the request. Even if it chose issue such an order, its effect would be limited in scope and fall far short of what the Clean Night Skies Act aims to achieve. Still, doing so would send a strong message to Congress that could help the Act's chances of becoming law in time. Lastly, we should continue to watch the ongoing experiment in state legislatures across the country. Several states have enacted pieces of light pollution legislation in the past 25 years. Others are considering doing so in the current or coming legislative terms. There are also opportunities to strengthen building and energy codes in the states, which sometimes govern how outdoor lighting is used. Change in U.S. Gross Domestic Product and emissions of six common air pollutants, 1980–2018. These data show that meaningful pollution reduction can be achieved without necessarily inflicting economic harm. Graph from resources.org; data sourced from the Federal Reserve Economic Data and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The road aheadSo where do we go from here? It pays to pursue an approach with many prongs. We shouldn't wait around for Congress to take action. For now, we can continue working from the bottom up from municipal councils to state legislatures. Advocates can raise the issue with members of Congress and their staffers, informing and educating them about both the problem and its solutions. We should state what it is we want from the federal government in the way of policy, and use that agenda to draft prospective legislation.

If all this sounds like a major undertaking, that's because it is. Big problems often become inter-generational efforts as one group works on the project for some years and then hands it off to their successors. The Clean Night Skies Act may take many years to become the law of the land. Its success requires sustained attention, which in turn means keeping eyes on the prize. The future of our nighttime environment may depend critically on its success.

0 Comments

Read More

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed