Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

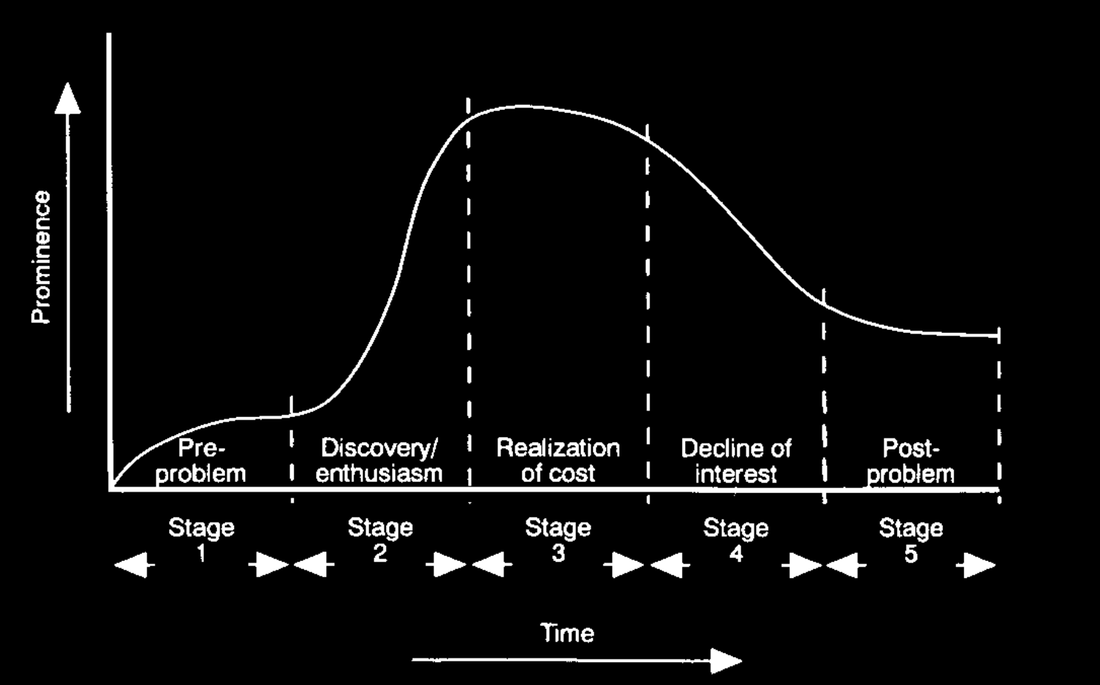

Grieving the dying dark9/30/2023 Image credit: Elias Rovielo 1349 words / 5-minute read We know a lot about the effects of light pollution on wildlife, the night sky, and in other areas but not as much about what it does to people. One can find some evidence for impacts having to do with physical health, wellbeing, and even social justice. Studies on mental health in particular are few, and most are about whether artificial light at night (ALAN) influences the occurrence of mental illness. Meanwhile, as humans concentrate into cities, they become distanced from nature. Some scholars speculate on whether separation from nature can have an adverse effect. Might something similar exist having to do with loss of nighttime darkness and routine access to the night sky? A loss like no otherSocial science has started to ask whether people experience a sense of grief or loss at environmental destruction. The Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht invented a word for it in 2005: solastalgia. Describing it as "the homesickness you have when you are still at home", Albrecht composed it from Latin and Greek words meaning 'comfort' and 'pain'/'suffering'/'grief'. It refers to both anxiety about the state of the environment both now and in the future. In June 2023, the journal Science published an issue with a special section about light pollution. Some 50 years after the term first appeared in its pages, light pollution appeared on its cover. Six review papers presented a summary of what we know about this issue from scientific, social and legal perspectives. In recent years, dark-sky activism and what is now called "community engagement" forged new connections among activists, researchers and others. Through this work I met Dr. Aparna Venkatesan, an astronomy professor and Co-Director of the Tracy Seeley Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of San Francisco. Besides her passion for the the study of the early universe, Aparna is a tireless advocate for diversity, equity and includion (DEI) in science and society. We also share a keen interest in the social consequences of space policy, about which we co-wrote a paper published last year in Nature Astronomy. We have had many discussions about these issues particularly since the dawn of the large satellite constellation era in 2019. We talked about all this in the broader context of loss of humanity's connections to the night sky. We also came to realize that the night sky makes up a kind of intangible cultural heritage, one worth protecting. Aparna suggested a word that parallels solastalgia in its derivation and meaning. "Noctalgia" is a neologism that combines roots for "night" and "pain" to suggest the sense of loss associated with the brightening of the night sky due to light pollution. In a broader sense, it encompasses any influence that changes the character of the night, including on the ground. In August we published an 'e-letter' in Science reacting to the articles in the earlier special section and introducing noctalgia to the world. We also posted the e-letter to the arXiv, a repository of scholarly literature on astronomy and other subjects. The media picked up on the idea shortly after and ran with it. The amount of coverage surprised us (see here, here, here and here). Clearly noctalgia struck a chord. Focusing attention on 'sky grief'Naming things can be an opening to talking about them with more honesty and authenticity. But we also hope that giving a voice to what some people now feel will help move them to take action. That action results from awareness that becomes a demand of society to take on and solve a problem. In turn, that relates to something called the 'issue attention cycle'. Anthony Downs was an American economist who specialized in public policy and public administration. In 1972 he wrote an influential paper called "Up and Down with Ecology — the Issue-Attention Cycle". In it, he argued that to solve social and environmental problems they had to capture and maintain public attention. He also described a cycle of steps from identification of the problem to post-solution effects that can start the cycle over again. As people discover light pollution, awareness rises. According to Downs' theory, some of them will decide that a real problem exists. If it maintains prominence for long enough, a critical mass will form and people will begin demanding solutions from decision makers. Yet it's arguable that the global dark-skies movement is still climbing the "hill of awareness" and that we are not at the peak yet. Even among those who become aware of light pollution, there's no guarantee that they will become part of this movement. Some who experience light pollution may write off the loss of the night as a consequence of progress and modernity. For example, people in developing economies may cite a need for outdoor lighting to enable safe transit at night and a nighttime economy. Given the colonial history in many such places, it's difficult to argue that they shouldn't have access to it. That's true even as we recognize the many ways that ALAN harms humans and nature. Some people might be motivated to do something about light pollution once they give voice (and a name) to the loss they have experienced. But that presumes that they have something to lose in the first place. As the world continues to urbanize, fewer people grow up in places where they can see the stars at night. It remains to be seen whether people who never had access to dark night skies grieve something that to them was never 'lost' in the first place. But that loss is especially acute for some people who have long suffered from deprivation. Indigenous, Aboriginal and First Nations people often live in places where the night sky is still accessible. In many instances, it looms large in their culture, folklore and religion. But these people often have little to do with creating the conditions that lead to light pollution. They also often have the least amount of political power in their countries and hence little ability to do anything about it. For many, the sense of loss is all too familiar. From noctalgia to actionThere is an old saying about how the pace of change determines outcomes: Toss a frog into a pot of boiling water and it will leap out to save itself. But toss a frog into a pot of cool water, gradually warming it up, and the frog will swim around until it boils to death.

People often recognize the severity of problems at different points in time. Some are 'early adopters' of such ideas, while others are laggards that don't get on board until late in the game. And as our world changes, what society considers acceptable levels of risk may shift. The loss of the night can prompt real, palpable grief in some people. But can noctalgia really prompt more people to take action on the problem of light pollution? We don't (yet) know whether the same is true of environmental problems more generally, or the role solastalgia plays. Meanwhile, people everywhere are straining under the weight of the many problems humanity faces. 'Crisis fatigue' is real, and it undermines efforts to solve those problems in definitive ways. But solving the problem of light pollution turns out to be remarkably simple and cost-effective. We don't lack a technological solution — one is in hand right now. It enables us to light the world at night well for human needs while minimizing the negative effects all that light has on the environment. By reducing or eliminating wasted light, we could get a handle on the situation in short order. Of more significance is that humanity desperately needs a win in the environmental realm. Were we to solve the problem of light pollution within a generation, the result might inspire confidence in out ability to take on bigger issues like climate change. But first, we have to finish climbing that 'hill of awareness' that moves people to action. If we do, it could be one of the defining environmental moments of the 21st century.

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

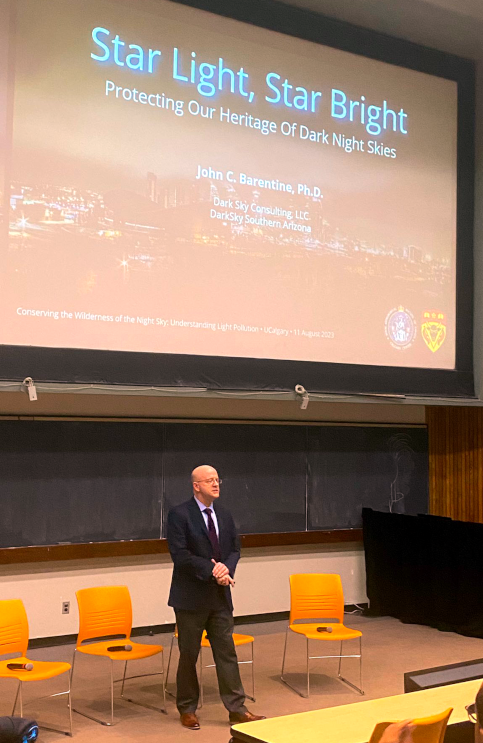

Conference report: ALAN 20239/1/2023 996 words / 4-minute read Summary: A diverse group of the world's light pollution experts recently met at the Artificial Light At Night 2023 conference. The main themes of the conference and important results presented there are reviewed, giving a sense of the research community's current direction. Many of the world's experts on light pollution recently met in Calgary, Canada, to discuss their latest findings. The Eighth International Conference on Artificial Light At Night (ALAN) was held in Calgary, Canada during 11-13 August 2023. We were there to learn about recent research results and new directions that ALAN science is heading. The ALAN conference series began in 2013. Starting with the 2018 edition, it occurs every other year, alternating with the Light Pollution: Theory, Modeling and Measurement conference. This year's edition saw its highest level of participation from the largest number of countries ever. 108 people attended in person on the University of Calgary campus and about 50 participated as virtual delegates. Group photo of the ALAN 2023 conference attendees This year’s attendees represented every populated continent except Africa. The participants represented some 28 countries. One-third of attendees were students, many of whom study ALAN as part of their graduate thesis or dissertation work. Despite some computer networking issues, virtual participation in the conference seemed strong. Besides to the in-person event in Calgary, a virtual poster session took place in late July using the Gather.town environment online. The ALAN Steering Committee accepted so many of the submitted abstracts that much of the in-person event ran in two parallel sessions. The broad topical content of the tracks was ALAN impacts on wildlife and ecology, and measurements and monitoring of light pollution. These tracks reflect where the majority of the research interest (and funding) are at this point in the field's history. There were fewer presentations about social science and public policy than in past years. Land acknowledgements were a frequent part of the proceedings. Former Calgary city councilor Brian Pincott explained that this is part of the ongoing truth and reconciliation process in Canada. "We have a lot to do to make sure our future includes everyone," Pincott said during his conference wrap-up on Sunday afternoon. Jennifer Howse (University of Calgary) gave the banquet talk, "Reclamation Under Alberta Skies", on Saturday night. Howse, a Métis woman, used her time to bridge the worlds of her Indigenous and European ancestry with the modern world in the context of her dark-sky work. She noted the importance in many Indigenous cultures of asking the question “How will people in seven generations live?” Howse also advised listeners to ponder that question in light of our activities that impact space and the night sky. It reminded attendees that the next frontier of dark-sky conservation involves social and environmental justice concerns. Diane Turnshek (Carnegie Mellon University) raised the issue of the increasing number of people who have never seen the Milky Way. It is therefore challenging to communicate with them about starry skies when this is not something they have directly experienced. Waleska Valle (Adler Planetarium) spoke about her experience working with youth in Chicago to identify the ways in which light pollution impacts their communities. And Doug Sam (University of Oregon) used the International Dark Sky Park designation effort at Mesa Verde National Park as a case study to examine such efforts through the theoretical framework of decolonization. “When we designate future IDSPs, we must involve native peoples as a matter of justice," Sam explained. Leora Radetzky (DesignLights Consortium) shows off samples of low-color temperature white LED lights. As usual, the scientific presentations were all high-quality and stimulated lively discussion. The main takeaways from the posters and talks include:

Friday night saw a successful public outreach event put on by the ALAN conference in coordination with the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Calgary Centre. About 300 people attended the event, which included an introductory talk about light pollution and a panel discussion with researchers. Afterward, attendees could view the night sky through telescopes set up on the University of Calgary campus. Dark Sky Consulting's John Barentine presents at the RASC Calgary Centre public event on Friday night. As participants began to disperse and head home beginning on Sunday, many reported how refreshing the experience was. ALAN 2013 was the first in-person conference in the series since 2018. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused the organizers to pivot to an online-only format. For many, the Calgary conference was the first time they saw their colleagues in person since 2019. Given that the research community is still small, the ALAN conferences feel more like village assemblies. A return to meaningful, in-person interactions supports the kind of collegiality that constantly draws students who want to make a career of night studies. It also supports collaborations that become friendships while yielding high-quality research results that push the field ahead. Announcement of the venue for the 2025 ALAN conference It is traditional to name the next host city at the conclusion of ALAN. On Sunday, attendees learned that the next meeting will be held in County Mayo, Republic of Ireland, in October 2025. Already many look forward to their next opportunity to present their work, reunite with old friends and meet new ones.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed