Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

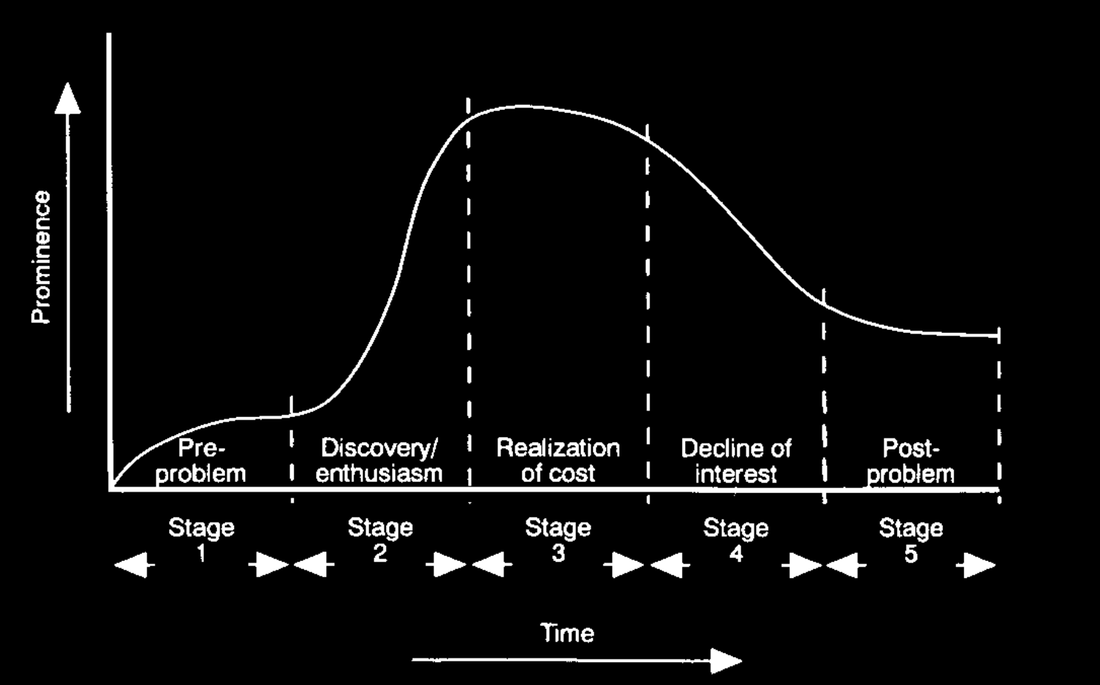

Grieving the dying dark9/30/2023 Image credit: Elias Rovielo 1349 words / 5-minute read We know a lot about the effects of light pollution on wildlife, the night sky, and in other areas but not as much about what it does to people. One can find some evidence for impacts having to do with physical health, wellbeing, and even social justice. Studies on mental health in particular are few, and most are about whether artificial light at night (ALAN) influences the occurrence of mental illness. Meanwhile, as humans concentrate into cities, they become distanced from nature. Some scholars speculate on whether separation from nature can have an adverse effect. Might something similar exist having to do with loss of nighttime darkness and routine access to the night sky? A loss like no otherSocial science has started to ask whether people experience a sense of grief or loss at environmental destruction. The Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht invented a word for it in 2005: solastalgia. Describing it as "the homesickness you have when you are still at home", Albrecht composed it from Latin and Greek words meaning 'comfort' and 'pain'/'suffering'/'grief'. It refers to both anxiety about the state of the environment both now and in the future. In June 2023, the journal Science published an issue with a special section about light pollution. Some 50 years after the term first appeared in its pages, light pollution appeared on its cover. Six review papers presented a summary of what we know about this issue from scientific, social and legal perspectives. In recent years, dark-sky activism and what is now called "community engagement" forged new connections among activists, researchers and others. Through this work I met Dr. Aparna Venkatesan, an astronomy professor and Co-Director of the Tracy Seeley Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of San Francisco. Besides her passion for the the study of the early universe, Aparna is a tireless advocate for diversity, equity and includion (DEI) in science and society. We also share a keen interest in the social consequences of space policy, about which we co-wrote a paper published last year in Nature Astronomy. We have had many discussions about these issues particularly since the dawn of the large satellite constellation era in 2019. We talked about all this in the broader context of loss of humanity's connections to the night sky. We also came to realize that the night sky makes up a kind of intangible cultural heritage, one worth protecting. Aparna suggested a word that parallels solastalgia in its derivation and meaning. "Noctalgia" is a neologism that combines roots for "night" and "pain" to suggest the sense of loss associated with the brightening of the night sky due to light pollution. In a broader sense, it encompasses any influence that changes the character of the night, including on the ground. In August we published an 'e-letter' in Science reacting to the articles in the earlier special section and introducing noctalgia to the world. We also posted the e-letter to the arXiv, a repository of scholarly literature on astronomy and other subjects. The media picked up on the idea shortly after and ran with it. The amount of coverage surprised us (see here, here, here and here). Clearly noctalgia struck a chord. Focusing attention on 'sky grief'Naming things can be an opening to talking about them with more honesty and authenticity. But we also hope that giving a voice to what some people now feel will help move them to take action. That action results from awareness that becomes a demand of society to take on and solve a problem. In turn, that relates to something called the 'issue attention cycle'. Anthony Downs was an American economist who specialized in public policy and public administration. In 1972 he wrote an influential paper called "Up and Down with Ecology — the Issue-Attention Cycle". In it, he argued that to solve social and environmental problems they had to capture and maintain public attention. He also described a cycle of steps from identification of the problem to post-solution effects that can start the cycle over again. As people discover light pollution, awareness rises. According to Downs' theory, some of them will decide that a real problem exists. If it maintains prominence for long enough, a critical mass will form and people will begin demanding solutions from decision makers. Yet it's arguable that the global dark-skies movement is still climbing the "hill of awareness" and that we are not at the peak yet. Even among those who become aware of light pollution, there's no guarantee that they will become part of this movement. Some who experience light pollution may write off the loss of the night as a consequence of progress and modernity. For example, people in developing economies may cite a need for outdoor lighting to enable safe transit at night and a nighttime economy. Given the colonial history in many such places, it's difficult to argue that they shouldn't have access to it. That's true even as we recognize the many ways that ALAN harms humans and nature. Some people might be motivated to do something about light pollution once they give voice (and a name) to the loss they have experienced. But that presumes that they have something to lose in the first place. As the world continues to urbanize, fewer people grow up in places where they can see the stars at night. It remains to be seen whether people who never had access to dark night skies grieve something that to them was never 'lost' in the first place. But that loss is especially acute for some people who have long suffered from deprivation. Indigenous, Aboriginal and First Nations people often live in places where the night sky is still accessible. In many instances, it looms large in their culture, folklore and religion. But these people often have little to do with creating the conditions that lead to light pollution. They also often have the least amount of political power in their countries and hence little ability to do anything about it. For many, the sense of loss is all too familiar. From noctalgia to actionThere is an old saying about how the pace of change determines outcomes: Toss a frog into a pot of boiling water and it will leap out to save itself. But toss a frog into a pot of cool water, gradually warming it up, and the frog will swim around until it boils to death.

People often recognize the severity of problems at different points in time. Some are 'early adopters' of such ideas, while others are laggards that don't get on board until late in the game. And as our world changes, what society considers acceptable levels of risk may shift. The loss of the night can prompt real, palpable grief in some people. But can noctalgia really prompt more people to take action on the problem of light pollution? We don't (yet) know whether the same is true of environmental problems more generally, or the role solastalgia plays. Meanwhile, people everywhere are straining under the weight of the many problems humanity faces. 'Crisis fatigue' is real, and it undermines efforts to solve those problems in definitive ways. But solving the problem of light pollution turns out to be remarkably simple and cost-effective. We don't lack a technological solution — one is in hand right now. It enables us to light the world at night well for human needs while minimizing the negative effects all that light has on the environment. By reducing or eliminating wasted light, we could get a handle on the situation in short order. Of more significance is that humanity desperately needs a win in the environmental realm. Were we to solve the problem of light pollution within a generation, the result might inspire confidence in out ability to take on bigger issues like climate change. But first, we have to finish climbing that 'hill of awareness' that moves people to action. If we do, it could be one of the defining environmental moments of the 21st century.

0 Comments

Read More

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed