Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

Conference report: ALAN 20239/1/2023 996 words / 4-minute read Summary: A diverse group of the world's light pollution experts recently met at the Artificial Light At Night 2023 conference. The main themes of the conference and important results presented there are reviewed, giving a sense of the research community's current direction. Many of the world's experts on light pollution recently met in Calgary, Canada, to discuss their latest findings. The Eighth International Conference on Artificial Light At Night (ALAN) was held in Calgary, Canada during 11-13 August 2023. We were there to learn about recent research results and new directions that ALAN science is heading. The ALAN conference series began in 2013. Starting with the 2018 edition, it occurs every other year, alternating with the Light Pollution: Theory, Modeling and Measurement conference. This year's edition saw its highest level of participation from the largest number of countries ever. 108 people attended in person on the University of Calgary campus and about 50 participated as virtual delegates. Group photo of the ALAN 2023 conference attendees This year’s attendees represented every populated continent except Africa. The participants represented some 28 countries. One-third of attendees were students, many of whom study ALAN as part of their graduate thesis or dissertation work. Despite some computer networking issues, virtual participation in the conference seemed strong. Besides to the in-person event in Calgary, a virtual poster session took place in late July using the Gather.town environment online. The ALAN Steering Committee accepted so many of the submitted abstracts that much of the in-person event ran in two parallel sessions. The broad topical content of the tracks was ALAN impacts on wildlife and ecology, and measurements and monitoring of light pollution. These tracks reflect where the majority of the research interest (and funding) are at this point in the field's history. There were fewer presentations about social science and public policy than in past years. Land acknowledgements were a frequent part of the proceedings. Former Calgary city councilor Brian Pincott explained that this is part of the ongoing truth and reconciliation process in Canada. "We have a lot to do to make sure our future includes everyone," Pincott said during his conference wrap-up on Sunday afternoon. Jennifer Howse (University of Calgary) gave the banquet talk, "Reclamation Under Alberta Skies", on Saturday night. Howse, a Métis woman, used her time to bridge the worlds of her Indigenous and European ancestry with the modern world in the context of her dark-sky work. She noted the importance in many Indigenous cultures of asking the question “How will people in seven generations live?” Howse also advised listeners to ponder that question in light of our activities that impact space and the night sky. It reminded attendees that the next frontier of dark-sky conservation involves social and environmental justice concerns. Diane Turnshek (Carnegie Mellon University) raised the issue of the increasing number of people who have never seen the Milky Way. It is therefore challenging to communicate with them about starry skies when this is not something they have directly experienced. Waleska Valle (Adler Planetarium) spoke about her experience working with youth in Chicago to identify the ways in which light pollution impacts their communities. And Doug Sam (University of Oregon) used the International Dark Sky Park designation effort at Mesa Verde National Park as a case study to examine such efforts through the theoretical framework of decolonization. “When we designate future IDSPs, we must involve native peoples as a matter of justice," Sam explained. Leora Radetzky (DesignLights Consortium) shows off samples of low-color temperature white LED lights. As usual, the scientific presentations were all high-quality and stimulated lively discussion. The main takeaways from the posters and talks include:

Friday night saw a successful public outreach event put on by the ALAN conference in coordination with the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Calgary Centre. About 300 people attended the event, which included an introductory talk about light pollution and a panel discussion with researchers. Afterward, attendees could view the night sky through telescopes set up on the University of Calgary campus. Dark Sky Consulting's John Barentine presents at the RASC Calgary Centre public event on Friday night. As participants began to disperse and head home beginning on Sunday, many reported how refreshing the experience was. ALAN 2013 was the first in-person conference in the series since 2018. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused the organizers to pivot to an online-only format. For many, the Calgary conference was the first time they saw their colleagues in person since 2019. Given that the research community is still small, the ALAN conferences feel more like village assemblies. A return to meaningful, in-person interactions supports the kind of collegiality that constantly draws students who want to make a career of night studies. It also supports collaborations that become friendships while yielding high-quality research results that push the field ahead. Announcement of the venue for the 2025 ALAN conference It is traditional to name the next host city at the conclusion of ALAN. On Sunday, attendees learned that the next meeting will be held in County Mayo, Republic of Ireland, in October 2025. Already many look forward to their next opportunity to present their work, reunite with old friends and meet new ones.

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

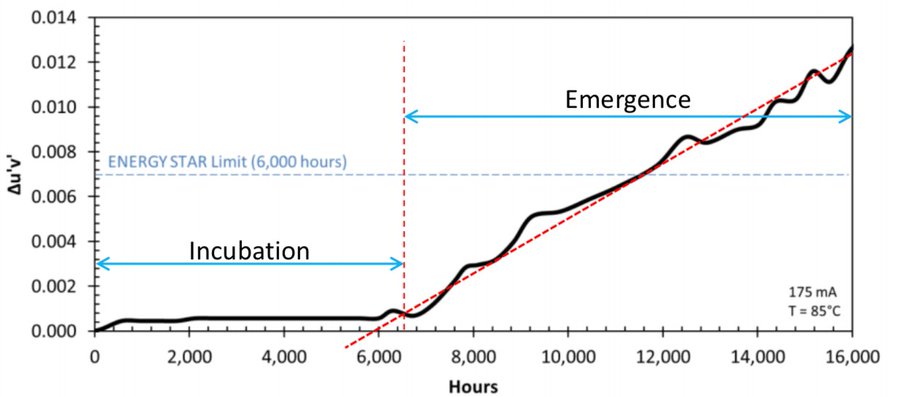

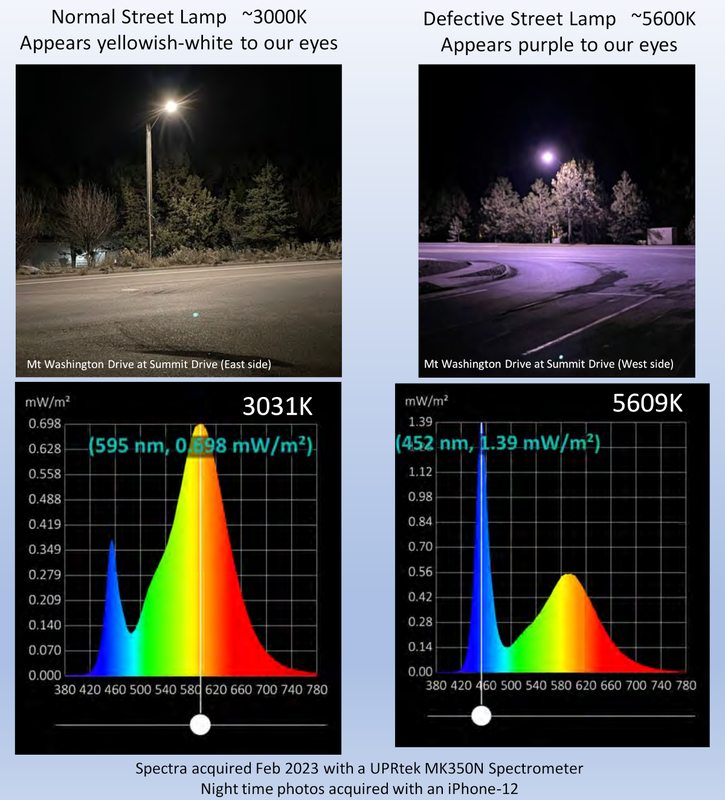

Why Are Streetlights Turning Purple?3/1/2023 Image credit: City of Manhattan, Kansas 1297 words / 5-minute read Summary: Chromaticity shift is affecting an increasing number of commercial outdoor lighting products. This may affect public perception of solid-state lighting and could change the nature of skyglow over cities. This post explores what it is, why it's happening, and what can be done about it. It sounds at first like an alien invasion. "The sky over the city of Vancouver was the color of a television tuned to a Prince concert." "I've had people call and ask if this was because it's Halloween, or because their football team in that area wears purple." "Street lights are mysteriously turning purple. Why is this happening?" In many parts of the United States, residents of cities are watching their new light-emitting diode (LED) street lights behave strangely. While they started out bright white, many are now turning an unsettling shade of purple. They have "spawned theories online about everything from vampires to vaccines". The truth is much more mundane. But as Business Insider notes, "when LED streetlights start changing color for no apparent reason, it's a visual cue that we might need to rethink, just a bit, how we build the future." Pretty or problematic?The lighting world has come up with a term for what many people are seeing close to home: 'chromaticity shift'. It's a fancy way of saying that the color of a light source is changing. The usual context of the term is in cases where that change is not part of the design of a lighting product. To understand why that matters, let's back up for a moment and look at how white LED light sources work. This technology has achieved incredible success, coming to dominate the lighting market in only about a decade. Its high energy efficiency and ability to be carefully controlled make it a lighting workhorse. But the light it produces isn't really "white". Underneath every white LED is a blue LED. Its blue light shines on a material called a phosphor, which has a particular chemical composition. Depending on the chemical mix, the material gives off light of other colors. Allowing for some of the blue light to leak through, the other colors add with it to give the sensation of "white" light. Some influences change the relationship between blue LED and the phosphor, or change the nature of the phosphor itself. The balance of colors emitted by the LED changes in turn. This can result in chromaticity shift. The perceived color of the resulting light depends on what has happened to the phosphor. Sometimes it happens when the material binding the phosphor swells or cracks. In other cases, heat changes the chemical characteristics of the phosphor. It's also possible for the capsule of the LED itself to scatter or absorb too much blue light. An example of outdoor lighting shifting to colors other than purple. These lights beneath the canopy at a filling station have shifted from white toward green, indicating that the phosphors in the LED capsules have oxidized. Whatever the cause, once chromaticity starts it's impossible to reverse. Correcting it requires replacement of the LED 'light engines'. Because these are now integrated into modern lighting products, it usually means replacing the entire light fixture. A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy report found that evidence for the shift starts to emerge after only about 8,000 hours of operation. While this time of "emergence" has increased, it is still far less than the expected lifetimes of LED lighting products. An often-quoted figure for the life of an LED chip is about 100,000 hours, or roughly 20 years of service. Chromaticity shift often shows up after about only two years. Lab measurements of white LEDs show a gradual shift in the color away from white after 6000-8000 hours of operation. Image credit: U.S. Department of Energy. So why are many white LEDs turning purple? It seems because of a manufacturing defect that causes the phosphor to pull away from the blue LED chip. In 2021, the manufacturer, American Electric Lighting, told the EdisonReport, a lighting trade publication, "The referenced 'blue light' effect occurred in a small percentage of AEL fixtures with components that have not been sold for several years. It is due to a spectral shift caused by phosphor displacement seen years after initial installation." It has since replaced many of the affected lights under warranty. Blues in the nightAt first the problem might seem only one of appearances. AEL stated that light produced by its products suffering chromaticity shift "is in no way harmful or unsafe." There is no reason to think that the purple lights are somehow dangerous to people. But there are real concerns about how their light affects the nighttime environment. White LED lights that have shifted toward purple are telling us that more of their blue light is escaping. This is especially evident in the images below kindly provided by Bill Kowalik and Cathie Flanigan of the Oregon Chapter of the International Dark-Sky Association. They show images of the visual appearance of both normal street lights in the city of Bend, Oregon, and those affected by chromaticity shift. For each image they show a spectrum of the light pictured. Comparing the two, it's clear that the purple lights emit much more blue light compared to light of all other colors. Bill and Cathie write, "The measurements show that for the purple lamp, the blue peak is about 2.5x stronger than the peak of green- yellow-red wavelengths. In the normal street lamp, the blue peak is about 1/2x the peak of the green-yellow-red." There is now a great deal of evidence that blue life is harmful to wildlife. In particular, in many species it disrupts the natural circadian rhythm necessary for wellbeing. We also know that blue light scatters better in the atmosphere than other colors. The strong scattering means that blue light is a main contributor to the phenomenon of skyglow over cities. Bluer light sources mean brighter night skies and fewer stars seen overhead. The impact of shifting street lights can be reduced if cities replace them promptly. Failed lights are usually covered by manufacturer warranties, and cities are entitled to replacements at no cost. But the saga of chromaticity shift follows reports of other, widespread LED street lighting failures. For example, in 2019 the city of Detroit, Michigan, settled a dispute with the manufacturer of almost 20,000 of its street lights that failed not long after installation. The settlement did not cover the full replacement cost, leaving the city on the hook to the tune of $3 million. Replacing shifting street lights may come with similar costs. The perils of being an early adopterThere is a bigger story here than just one of purple street lights. There are of course risks attendant to any emerging technology, some of which might not become apparent for years. Business Insider suggests that the problem for American Electric Lighting was sourcing poor-quality parts from overseas manufacturers: "Those vendors are typically building products at scale, trying to squeeze out every efficiency they can without infringing on the patents on the high-quality, higher-priced versions. Sometimes that makes for a less-good LED."

These are dollars-and-cents decisions for lighting manufacturers. In the last decade, market forces exerted a huge downward pressure on LED lighting prices. Converting the world's existing lighting to LED was a tremendous, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Responding to customer demand created supply issues, and companies looked toward what was both cheap and available. The quality of some of the electronic components used in their products simply wasn't high. And some companies are now obligated to provide very expensive replacements under warranty. These cautionary tales should inform the next generation of advanced lighting product development. It calls into question what other elements of the infrastructure of cities, now so deeply dependent on technology, may be next to fail. In our increasingly interconnected world, purple street lights are a metaphor for the ties that bind — and sometimes fail -- us. The color qualities of light are only one aspect of the decisions that local governments face when they decide to modernize their street lighting. For many tasked with making decisions, it can be a confusing topic to navigate. Our expertise and experience advising cities choosing new lighting can make the difference in the success of retrofit projects. Contact us today to find out how we can help your city. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed