Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

Image credit: Cottonbro Studio 1320 words / 5-minute read Summary: Although subject to widely held folk beliefs, the truth about how outdoor lighting and crime interact is very unsettled scientifically. This post examines the evidence, identifies shortcomings in current research and practice, and suggests the factors and considerations that really matter. Imagine that you are in an unfamiliar city, far from home. You're walking along a street that doesn't have much lighting, passing people you can't see very well. What kind of feeling does it cause you? For many people, it isn't a good one; for women in particular, the sense of fear can be crippling. Now imagine what would ease that fear. More lighting? How bright? What if it were as bright as daylight? How much light would it take to reassure you that it was safe to walk there? These are questions people have been asking for almost as long as there has been artificial lighting. Many people, at least in Western cultures, think that an association between darkness and crime is a given. This is in part built on folk beliefs that draw direct parallels: dark = bad, light = good. It's become part of our folklore, a kind of received wisdom that few question. But what does science say about all this? Is there an evidence-based case for lighting up the night in the name of safety? And what does it tell us about how we light the world now? Evidence in disarrayThe evidence about lighting crime is very unsettled. In its Artificial Light at Night: State of the Science 2023 report, DarkSky International puts it this way: "Certain studies reported crime reduction when lighting is added to outdoor spaces. [1] Others find either a negative effect, [2] no effect, [3-4] or mixed results. [5]" There is no obvious and consistent relationship between outdoor lighting and crime that shows up in the data. Rather, whether an experiment shows a positive or negative association between them depends very much on the details. We can then ask: why is the picture so unclear? For one thing, it's difficult to get lighting and crime studies funded. When funds are available, they sometimes come from lighting equipment manufacturers. While this does not itself render the results unreliable, it demands unusual transparency from researchers to avoid any hint of bias. Some studies are not subjected to peer review, instead appearing in the so-called 'grey literature'. And some are conducted outside the parameters of what are considered best research practices, such as pre-registration of trials. This makes it very difficult to interpret results of valid experiments and compare them against each other. Are the results reproducible? And would anyone hang their hat on this evidence? In fairness to the research community, it's difficult to design and conduct valid experiments. That's because crime is a human behavior subject to a complex psychology. The result is that many variables influence crime beyond the time of day and whether light is present at night. Studies on lighting and fear of crime often can't distinguish lighting from other effects. For example, in one study that considered how the intensity of lighting influenced public perceptions of outdoor spaces at night, the authors admitted that "if a location feels unsafe in daylight then it is likely to feel unsafe after dark, regardless of the light level." [6] And how much of this is real relative to what we know about crime incidence? In a problem that "seems reasonably unique to crime," [7] there is a significant difference in terms of how prevalent people think crime is relative to its actual prevalence. [8] People predisposed to expect crime in certain areas will likely never find satisfaction in the lighting conditions in those places. The bottom line is that almost all lighting and crime results are suspect to some extent. "Studies which purport to show large lighting benefit for public safety tend to be of poor scientific and statistical quality, done by those with poor scientific and statistical background," says Dr. Paul Marchant, a statistician and researcher based in the UK who has published extensively on the subject. "[Even] better quality, large temporal- and spatial-scale studies are unable to detect any public safety lighting benefit.” "Feelings of safety" and lighting for "reassurance"Another way of looking at the problem is to focus less on testing whether lighting deters or prevents crime and more on the effect it has on the observer. What makes people feel safe in outdoor spaces at night? Feelings of insecurity are very powerful and drive people toward high light levels because they "feel safe" in the same outdoor spaces during the daytime. Make no mistake: the feeling of fear is real and, for many people, visceral. [9] And for many of the same people, they think that they won't be safe unless outdoor lighting levels are like daylight. That implies light as a crime deterrent, based on the assumption that criminals are less likely to act if they think they will be seen by others. Even if the basis for that mechanism isn't true, it can have a profound effect on users of outdoor spaces at night. Researchers have considered the notion of "feelings of safety" (FoS) as a measurable quantity. In 2020, Alina Svechkina, Tamar Trop and Boris Portnov of the University of Haifa in Israel put volunteers into nighttime spaces in several Israeli cities. They varied the lighting conditions and then asked the volunteers to rate their sense of safety and security under each lighting treatment. Their results suggest that FoS rise the fastest with increasing lighting levels when going from no light to low intensity. [10] But FoS rapidly levels out when going toward higher light levels. In other words, it's a classic case of "diminishing returns": doubling the amount of light doesn't double FoS. Worse, the application of bright lighting in one area might have the result of moving crime around. Lisa Tompson (University of Waikato, New Zealand, and University College London) and coworkers found that the absence of street lighting on city streets in the UK "may prevent theft from vehicles, but there is a danger of offenses being temporally or spatially displaced." In other words, thieves might just move their nefarious activities to adjacent (and more brightly-lit) neighborhoods, or from overnight hours to the daytime. To reduce dependence on nighttime lighting in the interest of reducing light pollution while also ensuring public support for such measures, some lighting designers are turning to the notion of "reassurance" lighting. This kind of design targets lighting to tasks like recognition of faces and expressions while emphasizing uniformity and object detection. [11] What can we do?Fear of crime is real, and we should pay attention to it. Throwing facts and figures at people who experience that fear is unlikely to change their perception. Instead, the use of "lighting for reassurance" practices shows some promise. Surprisingly small amounts of light are useful for reassurance. But high light levels can make people feel like they're in a literal spotlight, compromising feelings of safety and making people feel more vulnerable. So what's the right answer? Bearing in mind that there is no magical formula that predicts the "right" lighting parameters, there are useful takeaways in all these points:

Marchant says, "It is hardly surprising that human beings are uneasy about the dark as we are a daytime species," while noting that nocturnal species likely feel just as uneasy about their existence in a world increasingly lit with artificial light at night. However, "[our] unease does not mean that a less brightly lit night is dangerous in terms of both crime and road traffic collisions." Using the best of what we know from science and practice can help create outdoor spaces at night that are not only beautiful and functional, but also empowering to users. References

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

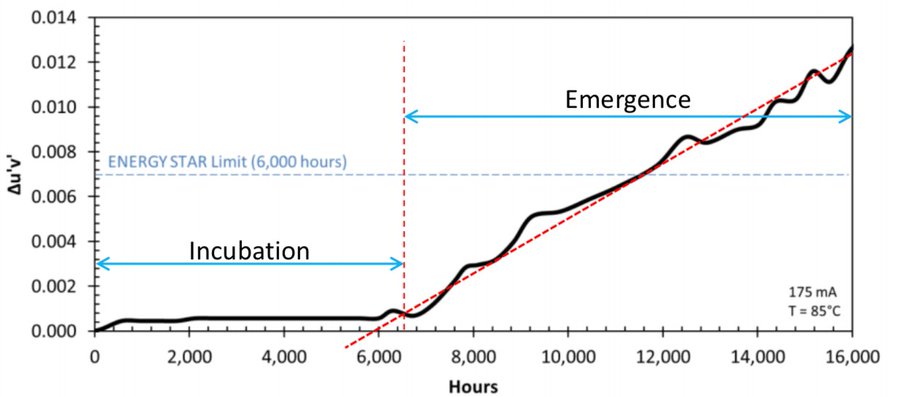

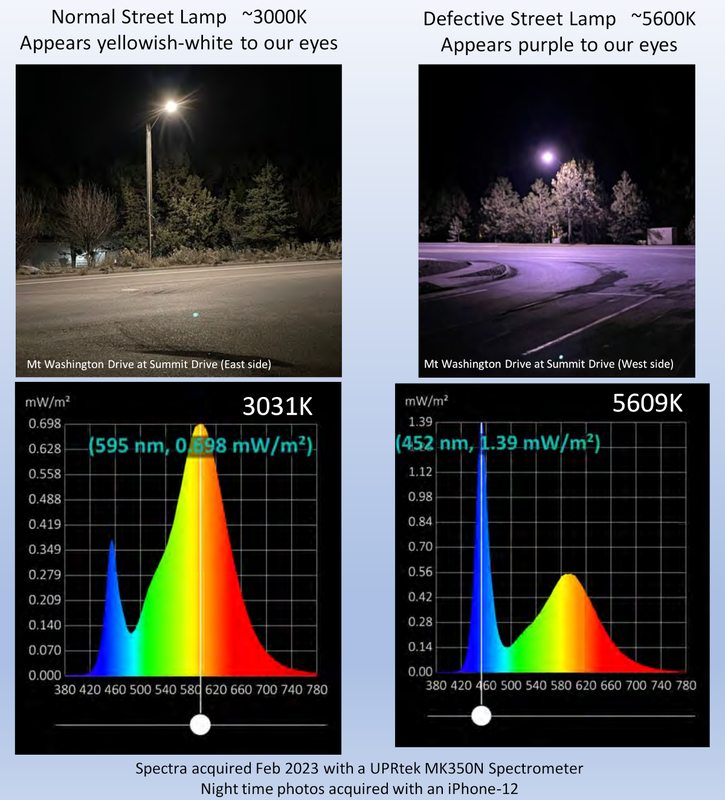

Why Are Streetlights Turning Purple?3/1/2023 Image credit: City of Manhattan, Kansas 1297 words / 5-minute read Summary: Chromaticity shift is affecting an increasing number of commercial outdoor lighting products. This may affect public perception of solid-state lighting and could change the nature of skyglow over cities. This post explores what it is, why it's happening, and what can be done about it. It sounds at first like an alien invasion. "The sky over the city of Vancouver was the color of a television tuned to a Prince concert." "I've had people call and ask if this was because it's Halloween, or because their football team in that area wears purple." "Street lights are mysteriously turning purple. Why is this happening?" In many parts of the United States, residents of cities are watching their new light-emitting diode (LED) street lights behave strangely. While they started out bright white, many are now turning an unsettling shade of purple. They have "spawned theories online about everything from vampires to vaccines". The truth is much more mundane. But as Business Insider notes, "when LED streetlights start changing color for no apparent reason, it's a visual cue that we might need to rethink, just a bit, how we build the future." Pretty or problematic?The lighting world has come up with a term for what many people are seeing close to home: 'chromaticity shift'. It's a fancy way of saying that the color of a light source is changing. The usual context of the term is in cases where that change is not part of the design of a lighting product. To understand why that matters, let's back up for a moment and look at how white LED light sources work. This technology has achieved incredible success, coming to dominate the lighting market in only about a decade. Its high energy efficiency and ability to be carefully controlled make it a lighting workhorse. But the light it produces isn't really "white". Underneath every white LED is a blue LED. Its blue light shines on a material called a phosphor, which has a particular chemical composition. Depending on the chemical mix, the material gives off light of other colors. Allowing for some of the blue light to leak through, the other colors add with it to give the sensation of "white" light. Some influences change the relationship between blue LED and the phosphor, or change the nature of the phosphor itself. The balance of colors emitted by the LED changes in turn. This can result in chromaticity shift. The perceived color of the resulting light depends on what has happened to the phosphor. Sometimes it happens when the material binding the phosphor swells or cracks. In other cases, heat changes the chemical characteristics of the phosphor. It's also possible for the capsule of the LED itself to scatter or absorb too much blue light. An example of outdoor lighting shifting to colors other than purple. These lights beneath the canopy at a filling station have shifted from white toward green, indicating that the phosphors in the LED capsules have oxidized. Whatever the cause, once chromaticity starts it's impossible to reverse. Correcting it requires replacement of the LED 'light engines'. Because these are now integrated into modern lighting products, it usually means replacing the entire light fixture. A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy report found that evidence for the shift starts to emerge after only about 8,000 hours of operation. While this time of "emergence" has increased, it is still far less than the expected lifetimes of LED lighting products. An often-quoted figure for the life of an LED chip is about 100,000 hours, or roughly 20 years of service. Chromaticity shift often shows up after about only two years. Lab measurements of white LEDs show a gradual shift in the color away from white after 6000-8000 hours of operation. Image credit: U.S. Department of Energy. So why are many white LEDs turning purple? It seems because of a manufacturing defect that causes the phosphor to pull away from the blue LED chip. In 2021, the manufacturer, American Electric Lighting, told the EdisonReport, a lighting trade publication, "The referenced 'blue light' effect occurred in a small percentage of AEL fixtures with components that have not been sold for several years. It is due to a spectral shift caused by phosphor displacement seen years after initial installation." It has since replaced many of the affected lights under warranty. Blues in the nightAt first the problem might seem only one of appearances. AEL stated that light produced by its products suffering chromaticity shift "is in no way harmful or unsafe." There is no reason to think that the purple lights are somehow dangerous to people. But there are real concerns about how their light affects the nighttime environment. White LED lights that have shifted toward purple are telling us that more of their blue light is escaping. This is especially evident in the images below kindly provided by Bill Kowalik and Cathie Flanigan of the Oregon Chapter of the International Dark-Sky Association. They show images of the visual appearance of both normal street lights in the city of Bend, Oregon, and those affected by chromaticity shift. For each image they show a spectrum of the light pictured. Comparing the two, it's clear that the purple lights emit much more blue light compared to light of all other colors. Bill and Cathie write, "The measurements show that for the purple lamp, the blue peak is about 2.5x stronger than the peak of green- yellow-red wavelengths. In the normal street lamp, the blue peak is about 1/2x the peak of the green-yellow-red." There is now a great deal of evidence that blue life is harmful to wildlife. In particular, in many species it disrupts the natural circadian rhythm necessary for wellbeing. We also know that blue light scatters better in the atmosphere than other colors. The strong scattering means that blue light is a main contributor to the phenomenon of skyglow over cities. Bluer light sources mean brighter night skies and fewer stars seen overhead. The impact of shifting street lights can be reduced if cities replace them promptly. Failed lights are usually covered by manufacturer warranties, and cities are entitled to replacements at no cost. But the saga of chromaticity shift follows reports of other, widespread LED street lighting failures. For example, in 2019 the city of Detroit, Michigan, settled a dispute with the manufacturer of almost 20,000 of its street lights that failed not long after installation. The settlement did not cover the full replacement cost, leaving the city on the hook to the tune of $3 million. Replacing shifting street lights may come with similar costs. The perils of being an early adopterThere is a bigger story here than just one of purple street lights. There are of course risks attendant to any emerging technology, some of which might not become apparent for years. Business Insider suggests that the problem for American Electric Lighting was sourcing poor-quality parts from overseas manufacturers: "Those vendors are typically building products at scale, trying to squeeze out every efficiency they can without infringing on the patents on the high-quality, higher-priced versions. Sometimes that makes for a less-good LED."

These are dollars-and-cents decisions for lighting manufacturers. In the last decade, market forces exerted a huge downward pressure on LED lighting prices. Converting the world's existing lighting to LED was a tremendous, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Responding to customer demand created supply issues, and companies looked toward what was both cheap and available. The quality of some of the electronic components used in their products simply wasn't high. And some companies are now obligated to provide very expensive replacements under warranty. These cautionary tales should inform the next generation of advanced lighting product development. It calls into question what other elements of the infrastructure of cities, now so deeply dependent on technology, may be next to fail. In our increasingly interconnected world, purple street lights are a metaphor for the ties that bind — and sometimes fail -- us. The color qualities of light are only one aspect of the decisions that local governments face when they decide to modernize their street lighting. For many tasked with making decisions, it can be a confusing topic to navigate. Our expertise and experience advising cities choosing new lighting can make the difference in the success of retrofit projects. Contact us today to find out how we can help your city. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed