Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

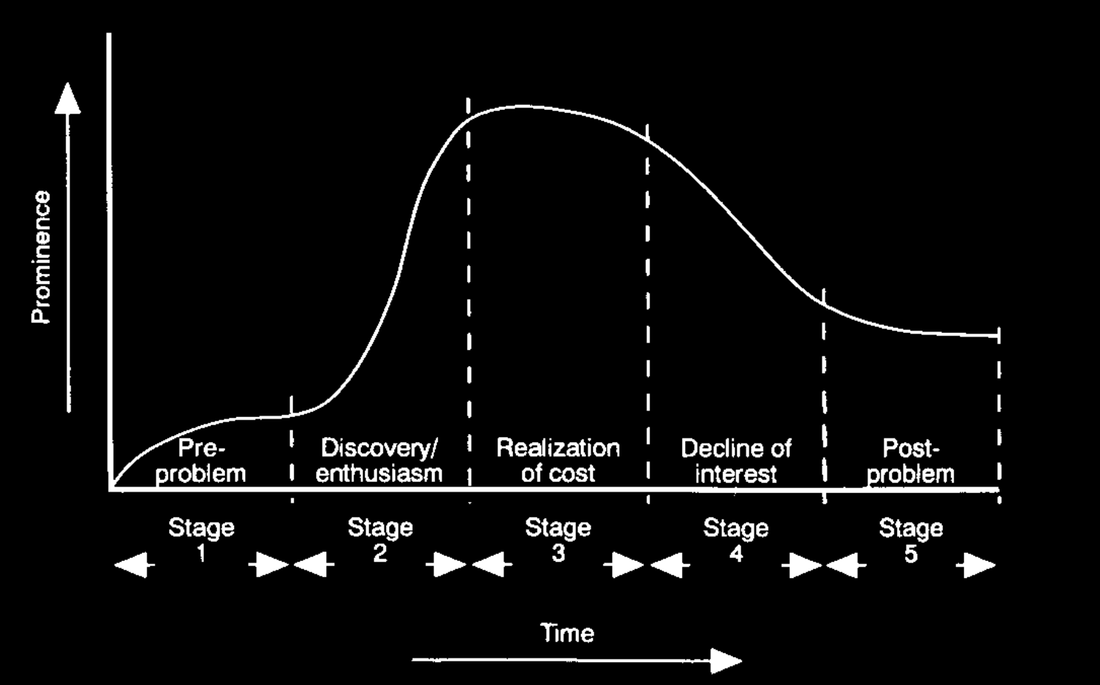

Grieving the dying dark9/30/2023 Image credit: Elias Rovielo 1349 words / 5-minute read We know a lot about the effects of light pollution on wildlife, the night sky, and in other areas but not as much about what it does to people. One can find some evidence for impacts having to do with physical health, wellbeing, and even social justice. Studies on mental health in particular are few, and most are about whether artificial light at night (ALAN) influences the occurrence of mental illness. Meanwhile, as humans concentrate into cities, they become distanced from nature. Some scholars speculate on whether separation from nature can have an adverse effect. Might something similar exist having to do with loss of nighttime darkness and routine access to the night sky? A loss like no otherSocial science has started to ask whether people experience a sense of grief or loss at environmental destruction. The Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht invented a word for it in 2005: solastalgia. Describing it as "the homesickness you have when you are still at home", Albrecht composed it from Latin and Greek words meaning 'comfort' and 'pain'/'suffering'/'grief'. It refers to both anxiety about the state of the environment both now and in the future. In June 2023, the journal Science published an issue with a special section about light pollution. Some 50 years after the term first appeared in its pages, light pollution appeared on its cover. Six review papers presented a summary of what we know about this issue from scientific, social and legal perspectives. In recent years, dark-sky activism and what is now called "community engagement" forged new connections among activists, researchers and others. Through this work I met Dr. Aparna Venkatesan, an astronomy professor and Co-Director of the Tracy Seeley Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of San Francisco. Besides her passion for the the study of the early universe, Aparna is a tireless advocate for diversity, equity and includion (DEI) in science and society. We also share a keen interest in the social consequences of space policy, about which we co-wrote a paper published last year in Nature Astronomy. We have had many discussions about these issues particularly since the dawn of the large satellite constellation era in 2019. We talked about all this in the broader context of loss of humanity's connections to the night sky. We also came to realize that the night sky makes up a kind of intangible cultural heritage, one worth protecting. Aparna suggested a word that parallels solastalgia in its derivation and meaning. "Noctalgia" is a neologism that combines roots for "night" and "pain" to suggest the sense of loss associated with the brightening of the night sky due to light pollution. In a broader sense, it encompasses any influence that changes the character of the night, including on the ground. In August we published an 'e-letter' in Science reacting to the articles in the earlier special section and introducing noctalgia to the world. We also posted the e-letter to the arXiv, a repository of scholarly literature on astronomy and other subjects. The media picked up on the idea shortly after and ran with it. The amount of coverage surprised us (see here, here, here and here). Clearly noctalgia struck a chord. Focusing attention on 'sky grief'Naming things can be an opening to talking about them with more honesty and authenticity. But we also hope that giving a voice to what some people now feel will help move them to take action. That action results from awareness that becomes a demand of society to take on and solve a problem. In turn, that relates to something called the 'issue attention cycle'. Anthony Downs was an American economist who specialized in public policy and public administration. In 1972 he wrote an influential paper called "Up and Down with Ecology — the Issue-Attention Cycle". In it, he argued that to solve social and environmental problems they had to capture and maintain public attention. He also described a cycle of steps from identification of the problem to post-solution effects that can start the cycle over again. As people discover light pollution, awareness rises. According to Downs' theory, some of them will decide that a real problem exists. If it maintains prominence for long enough, a critical mass will form and people will begin demanding solutions from decision makers. Yet it's arguable that the global dark-skies movement is still climbing the "hill of awareness" and that we are not at the peak yet. Even among those who become aware of light pollution, there's no guarantee that they will become part of this movement. Some who experience light pollution may write off the loss of the night as a consequence of progress and modernity. For example, people in developing economies may cite a need for outdoor lighting to enable safe transit at night and a nighttime economy. Given the colonial history in many such places, it's difficult to argue that they shouldn't have access to it. That's true even as we recognize the many ways that ALAN harms humans and nature. Some people might be motivated to do something about light pollution once they give voice (and a name) to the loss they have experienced. But that presumes that they have something to lose in the first place. As the world continues to urbanize, fewer people grow up in places where they can see the stars at night. It remains to be seen whether people who never had access to dark night skies grieve something that to them was never 'lost' in the first place. But that loss is especially acute for some people who have long suffered from deprivation. Indigenous, Aboriginal and First Nations people often live in places where the night sky is still accessible. In many instances, it looms large in their culture, folklore and religion. But these people often have little to do with creating the conditions that lead to light pollution. They also often have the least amount of political power in their countries and hence little ability to do anything about it. For many, the sense of loss is all too familiar. From noctalgia to actionThere is an old saying about how the pace of change determines outcomes: Toss a frog into a pot of boiling water and it will leap out to save itself. But toss a frog into a pot of cool water, gradually warming it up, and the frog will swim around until it boils to death.

People often recognize the severity of problems at different points in time. Some are 'early adopters' of such ideas, while others are laggards that don't get on board until late in the game. And as our world changes, what society considers acceptable levels of risk may shift. The loss of the night can prompt real, palpable grief in some people. But can noctalgia really prompt more people to take action on the problem of light pollution? We don't (yet) know whether the same is true of environmental problems more generally, or the role solastalgia plays. Meanwhile, people everywhere are straining under the weight of the many problems humanity faces. 'Crisis fatigue' is real, and it undermines efforts to solve those problems in definitive ways. But solving the problem of light pollution turns out to be remarkably simple and cost-effective. We don't lack a technological solution — one is in hand right now. It enables us to light the world at night well for human needs while minimizing the negative effects all that light has on the environment. By reducing or eliminating wasted light, we could get a handle on the situation in short order. Of more significance is that humanity desperately needs a win in the environmental realm. Were we to solve the problem of light pollution within a generation, the result might inspire confidence in out ability to take on bigger issues like climate change. But first, we have to finish climbing that 'hill of awareness' that moves people to action. If we do, it could be one of the defining environmental moments of the 21st century.

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

Image credit: Daniel Mennerich 1182 words / 5-minute read Summary: Most efforts to reduce light pollution to date have focused on the public sector. But as night skies continue to brighten around the world, private enterprise can play in protecting dark night skies. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environment, social, and governance (ESG) principles may be powerful — and thus far unappreciated — levers on the problem. A recent paper in the journal Science made a splash in the world media. Headlines included "It's Getting Harder and Harder to See the Stars", "Starry Nights Are Disappearing", and "As 'skyglow' grows, study documents glaring global light pollution". The paper contained a startling result: in some parts of the world, the brightness of the night sky doubles every eight years. It represented a big increase compared to the rate of change reported as recently as 2017. Light pollution is a problem in many parts of our world, its harms now thoroughly documented. Available technical solutions are cost effective, but the social and political will to put them into practice are missing. Laws and regulations can help, but they only go so far given that they are often not enforced well. After governments, private enterprises are some of the most prolific light polluters in many communities. At the same time, those enterprises are finding that their environmental bona fides are increasingly scrutinized. Can the concepts of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environment, social, and governance (ESG) nudge some companies toward doing better? Beyond the buzzwords: what are CSR and ESG?CSR and ESG are hot topics in the global corporate world. But what do they really mean? CSR establishes values and sets an agenda, while ESG turns that agenda into goals with measurable impact. In a sense, CSR makes up the "S" ("social") in ESG by operationalizing the vision that CSR establishes. The actions of early 20th century industrialists like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie exemplify CSR. They spent billions of dollars on social causes, the legacy of which remains with us to this day. ESG traces its roots to the South African anti-apartheid movement that began in the late 1950s. It only became well known in 2006 when the United Nations launched the "Principles for Responsible Investment." CSR is qualitative due to the many nuances of measuring social impact. ESG criteria tend to consist of quantitative metrics. It provides a way for companies, investors and the public to check how well companies stick to the sustainability and corporate responsibility goals they set. The current understanding of ESG considers the environment a stakeholder in all businesses. No particular industry or sector is exempt. This framework is not immune to criticism. A major disadvantage of CSR and ESG is that small businesses shoulder much of its costs. Some critics contend that they undermine the primary aim of business, which is to create (financial) value for shareholders. They can also draw unwanted scrutiny over ever aspect of a company's business. And in some cases, CSR/ESG initiatives can distract from the need for meaningful, systemic change. Why companies careThe corporate world now ignores CSR and ESG at its own peril. Corporate boards increasingly seek advice on how to pursue these ideas. Some now see environmental concerns as among the stakeholders that their business affects. But much of the pressure to do so still comes from the outside. One recent survey found that almost three-fourths institutional investors do not trust companies to achieve their stated sustainability and ESG goals. Investors and regulators alike are applying pressure on companies. And it's becoming hard for them to hide the environmental and social harms associated with their activities. What about forces operating inside organizations? There is some evidence that companies prioritizing CSR and ESG principles have increased employee productivity and reduced turnover. Other data suggest that consumers, especially younger people, prefer to buy from companies that exhibit a strong sense of social responsibility. Failing to recognize this can even cost companies more in the long run. How CSR and ESG may influence light pollutionLight pollution is an environmental issue at its core. It involves many known and suspected hazards to plants, animals and even people. With each passing year, the weight of the evidence grows bigger. And because the world still produces some 80 percent of its electricity from fossil fuel sources, light pollution is also a climate issue. Light pollution arguably harms businesses' environmental stakeholders, yet it costs little to nothing to undo the damage. Many businesses will find it even saves them money to reduce their artificial light at night emissions in both their supply chains and at their facilities. Companies that fail to take advantage of these savings may be seen — pardon the pun — in a bad light. It may lead to accusations that they only care about higher-profile environmental issues. In turn, that implies that their assessments of environmental stakeholder needs are inadequate. Wherever companies operate, they extract profits from those territories and communities. As the social significance of climate change rises, it is a disadvantage when the public perceives a company is doing harm rather than good. Those that do considerable business with governments may find these concerns turn into requirements. Planning ahead to be able to react quickly to a changing business landscape conveys a clear advantage. There is even a nexus among ESG, land use planning, the public regulatory regime, and dark skies. In countries like Wales and New Zealand, large territories are under management as International Dark Sky Reserves. Both the central governments and local councils in those places are proactive in framing light pollution as an environmental concern. From theory to actionWhat can companies do? They should put their own houses in order first. Audits of lighting practices and policies can reveal opportunities to reduce waste and lower light emissions. For instance, a retailer with large distribution centers might find that over-lighting of facilities threatens worker safety. A review of their business models may show elements that generate significant light pollution. Changes can reduce their impact without undermining those models and the profits they drive. Companies that leverage the low cost of making these improvements will find that they can't afford not to do it. One simple blueprint for developing CSR and ESG goals is to ensure corporate actions adhere to the Five Principles for Responsible Outdoor Lighting. This series of statements prioritizes protection of the nighttime environment by prescribing simple lighting concepts. It also suggests metrics that companies can use to chart their progress. What holds back progress in this arena? As with much of the wider world of dark-sky advocacy, the main missing piece of the puzzle is awareness. Corporate boards that become aware of the harms of light pollution are more likely to develop policies that commit to its reduction. Investors and consumers can be important influences that raise awareness. Solutions may be as much bottom-up as top-down. As the world becomes more socialized to the related challenges of climate change and sustainability, so it may be more likely to discover light pollution. Companies can either recognize this and act on it or risk exposure as a major source of the problem. Those that choose action will find the relevant technology advanced, the solutions plentiful, and the value proposition powerful. Every company can benefit from a review of its policies and practices relating to outdoor lighting. Contact us today to learn how we can help your business understand its light pollution impact. Thanks to Lee Mauger for helpful discussions as this post was coming together.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed