Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

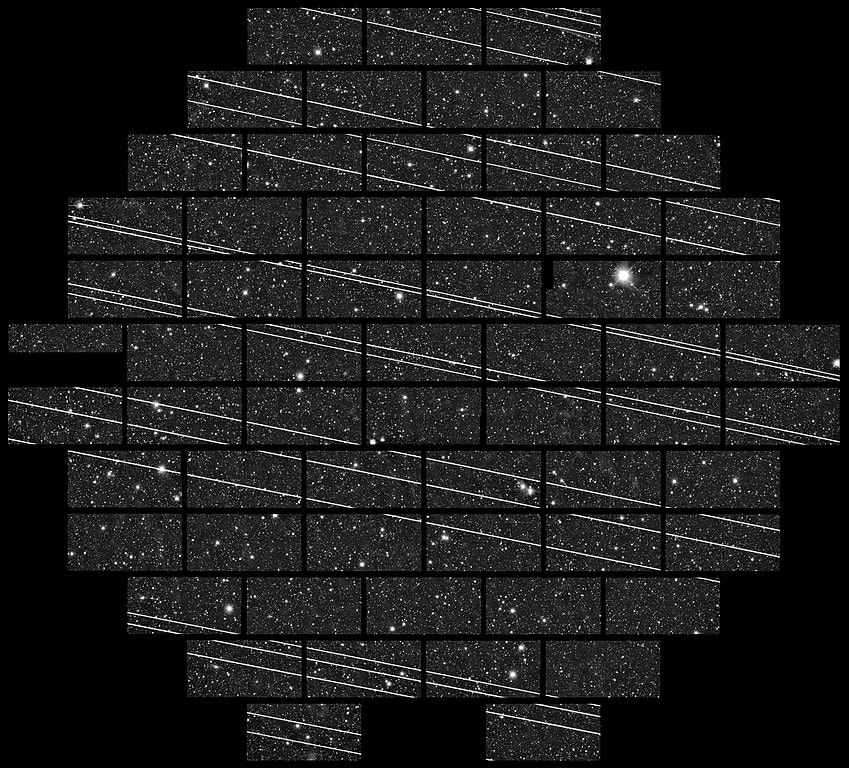

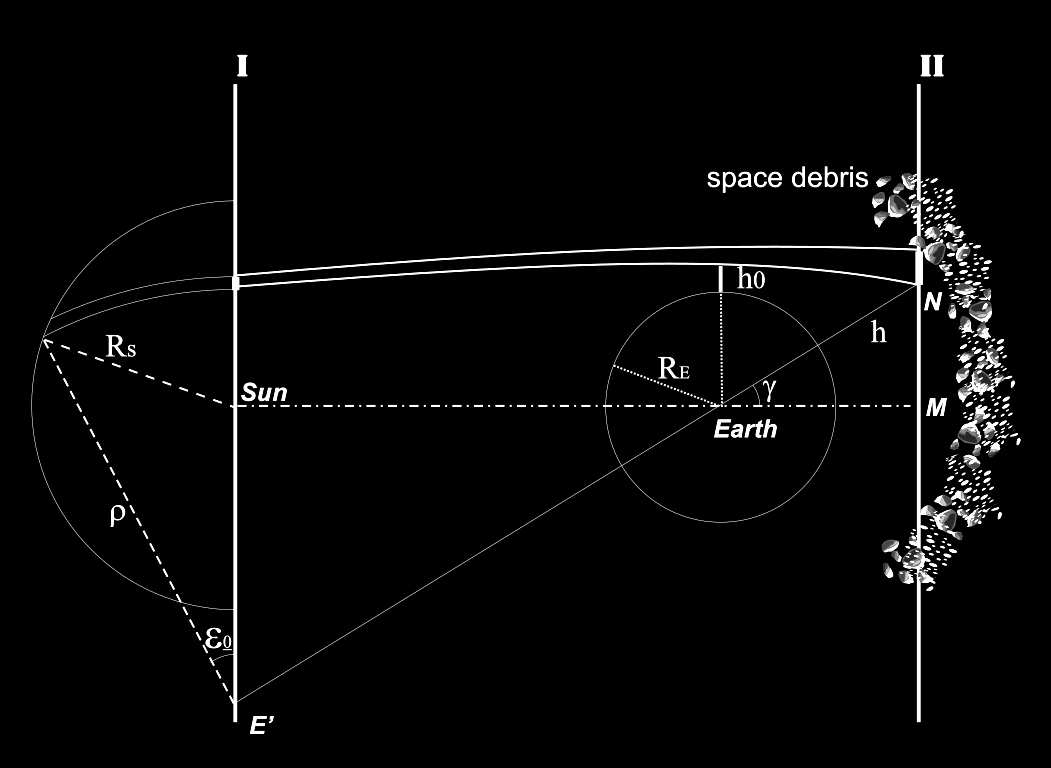

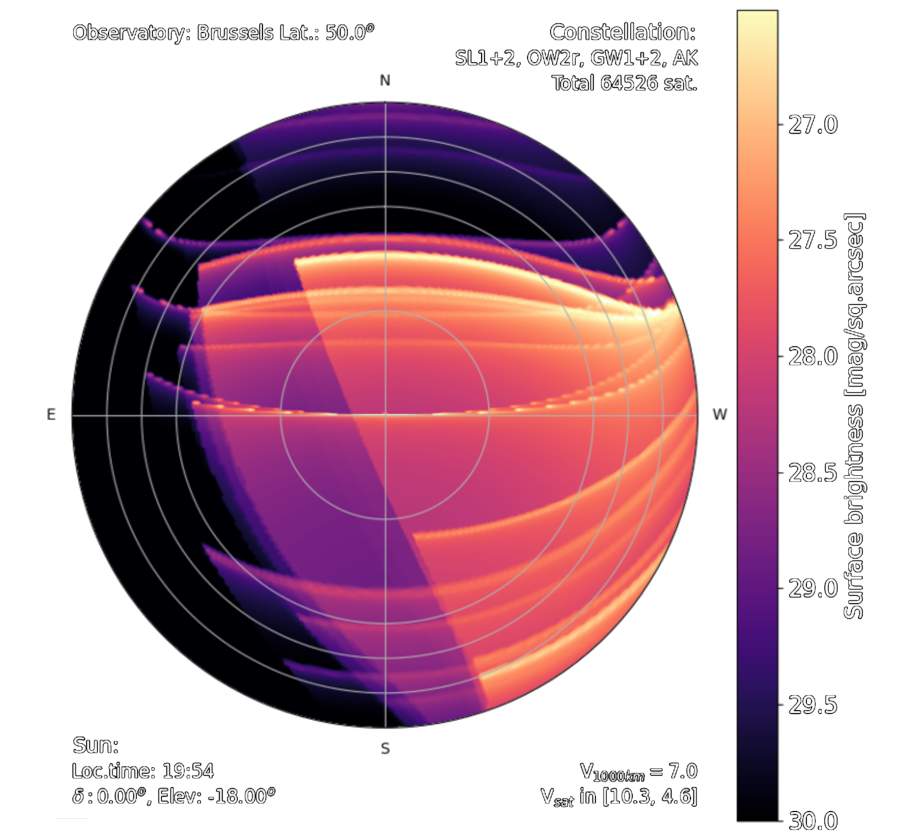

Image credit: Mike Lewinski 1112 words / 5-minute read Summary: The orbital space around the Earth is filling up with thousands of new satellites. This is changing the appearance of the night sky, but it still pales in comparison to the effects of ground-based light pollution. In January, we wrote about new research showing that the world at night is lighting up fast. At the same time, something else is happening that may change the nighttime world as much. The orbital region around the Earth is filling up due to increasing activity in the commercial space sector. Thousands of new satellites, and the debris they create, may change the night sky forever. But how significant is the problem, and what can we do about it? Satellites have been around for almost seven decades. For years, countries launched them one at a time for specific purposes. Most satellites served to relay communications across continents at the speed of light. In the 1960s, engineers began to experiment with flying small, coordinated groups of satellites. Called "constellations", these groups performed specific tasks like relaying time signals. This is the basis for modern conveniences like the Global Positioning System, or GPS. By the end of the 2010s there were a few thousand satellites overhead. These ranged in altitude from a few hundred kilometers to about 37,000 kilometers. Those highest satellites, in "geosynchronous" orbits, can dwell indefinitely over any particular place. Their distance, coupled with the speed of light, made for somewhat slow communications. But times were changing. The cost of launching payloads into space was dropping. The uses of orbital space are changingIn 2019, the American company SpaceX launched the first group of satellites representing a new use of outer space. Called "Starlink", the project aimed to provide high-speed Internet to almost every place on Earth. The company plans to deploy up to 35,000 Starlink satellites by the end of the 2020s. Others, following suit, have proposed as many as 393,000 more. These so-called "megaconstellations" are unprecedented in the use of outer space by humans. There are many concerns about how these activities in space will affect our planet. To maintain these large numbers of satellites in orbit, launches will become an almost daily event. Rocket launches produce materials that foul the air and water, and they can damage launch sites. Satellites coming back to Earth will deposit significant amount of metal in the upper atmosphere. And the current best practice in disposing of what returns to Earth is to dump it in the ocean. Little in the way of international law governs these activities. The current legal framework descends from the Outer Space Treaty (OST). Signed in 1967, much of the treaty speaks to the peaceful exploration of space. It prohibits territorial claims on other worlds and the deployment of nuclear weapons in space. And it makes countries liable for damages caused by spacecraft launched from their territories. But the OST does not envision uses of space like satellite megaconstellations. The governance system the OST establishes is slow to act. And countries downplay environmental concerns as they rush to cash in on the megaconstellation phenomenon. All the while, the risks of space debris are growing. Congested orbital space increases the chances of collisions between satellites. The space is also filling with debris shed by satellites and discarded items like used rocket bodies. These objects threaten new collisions and make space more dangerous. Some speculate that the generation of space debris could quickly spiral out of control. Bright streaks from Starlink satellites cross the field of view of the the DECam detectors on the Blanco 4-meter telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in this November 2019 image. Image credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/DECam DELVE Survey Astronomers grew nervous after the first Starlink launch. Strings of bright objects appeared in the night sky around the world. Reflecting sunlight to the night side of Earth, the satellites began appearing in telescope data. Radio transmissions from satellite to ground interfered with sensitive radio telescopes. The astronomical community organized a series of conferences in 2020-2021 to discuss the problem. They recruited participation from the space industry to find creative solutions to the problem. One result is the establishment of the Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky from Satellite Constellation Interference. More than just bright streaks of lightThere is another way in which these large satellite constellations may affect the night sky. The rules of optics dictate the size of the smallest object that an optical system can resolve. Telescopes on the ground can resolve objects that are a little smaller than a meter in size. Smaller objects are not resolved, but their light still makes it into telescopes (and human eyes) at night. The result is a faint, diffuse glow across the night sky. This raises the brightness of the sky background, much like skyglow from light sources on the ground. In 2021, researchers published a simple model to quantify how much light this contributes to the night sky. They made estimates for conditions before the first Starlink launch in 2019. The results suggested that by that time, satellites and debris ('space objects') raised the sky brightness by 10% above its natural level. A model for night sky brightness due to objects in orbit around the Earth. Light emitted by the Sun (shown as a semi-circle at left) is refracted through the Earth's atmosphere, where it illuminates a belt of objects of a given size distribution (right) above the planet. The model sums up the diffuse light contributions from all the objects visible from the observer's location. Figure 1 in Kocifaj et al. (2021). As the night sky gets brighter, it becomes difficult to see cosmic light from beyond. Raising the background level lowers the contrast between the sky and objects like stars and galaxies. For casual stargazers, it means seeing fewer stars at night. They may also miss faint phenomena like weak aurorae and dim meteors. Professional astronomers stand to lose some of their data. This means either they do less science or spend more money to build even bigger telescopes. This may have serious consequences in coming decades. Another group published a study the following year that identified small debris particles as the problem. While they're much smaller objects than satellites, there are very many more of them. Given their small sizes, even the world's largest telescopes can't resolve them. The scientists concluded that if the generation of new debris can be minimized, the effect on the night sky might be minimal. A prediction for the night sky brightness due to space objects over the city of Brussels, Belgium, assuming over 64,000 satellites in orbit around the Earth by about 2030. This is an all-sky view where the horizon runs around the outer edge of the circle at the zenith (top of the sky) is at the center. The false colors show the expected surface brightness of the night sky; the bright bands correspond to orbital 'shells' inhabited by the largest numbers of satellites. Figure 11a from Bassa, Hainaut and Galadí-Enríquez (2022). A small effect — for nowThe expected effect from space objects is small for now. Compared to skyglow in and near cities, it's almost negligible. The problem will be most noticeable in the least light-polluted places, like astronomical observatory sites. But that depends very much on what the future of space debris production is like. If satellites don't grind each other into dust through collisions, the worst outcomes may be avoided.

A combination of design and operations improvements and public policy changes is likely needed. This may involve changes to our understanding of what the "environment" is by taking a fresh look at our policies. While some space companies are willing participants in these efforts, others have yet to come to the table. There is still much about this story that causes alarm. The night sky is changing, both from light pollution on the ground and, to a lesser extent, from space. While the problem of ground-based light pollution has demonstrated solutions, we don't yet have the answers for satellites. In both situations, the decisions we make today as a society will most certainly affect the future of our night sky.

0 Comments

Read More

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed