Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

Conference report: ALAN 20239/1/2023 996 words / 4-minute read Summary: A diverse group of the world's light pollution experts recently met at the Artificial Light At Night 2023 conference. The main themes of the conference and important results presented there are reviewed, giving a sense of the research community's current direction. Many of the world's experts on light pollution recently met in Calgary, Canada, to discuss their latest findings. The Eighth International Conference on Artificial Light At Night (ALAN) was held in Calgary, Canada during 11-13 August 2023. We were there to learn about recent research results and new directions that ALAN science is heading. The ALAN conference series began in 2013. Starting with the 2018 edition, it occurs every other year, alternating with the Light Pollution: Theory, Modeling and Measurement conference. This year's edition saw its highest level of participation from the largest number of countries ever. 108 people attended in person on the University of Calgary campus and about 50 participated as virtual delegates. Group photo of the ALAN 2023 conference attendees This year’s attendees represented every populated continent except Africa. The participants represented some 28 countries. One-third of attendees were students, many of whom study ALAN as part of their graduate thesis or dissertation work. Despite some computer networking issues, virtual participation in the conference seemed strong. Besides to the in-person event in Calgary, a virtual poster session took place in late July using the Gather.town environment online. The ALAN Steering Committee accepted so many of the submitted abstracts that much of the in-person event ran in two parallel sessions. The broad topical content of the tracks was ALAN impacts on wildlife and ecology, and measurements and monitoring of light pollution. These tracks reflect where the majority of the research interest (and funding) are at this point in the field's history. There were fewer presentations about social science and public policy than in past years. Land acknowledgements were a frequent part of the proceedings. Former Calgary city councilor Brian Pincott explained that this is part of the ongoing truth and reconciliation process in Canada. "We have a lot to do to make sure our future includes everyone," Pincott said during his conference wrap-up on Sunday afternoon. Jennifer Howse (University of Calgary) gave the banquet talk, "Reclamation Under Alberta Skies", on Saturday night. Howse, a Métis woman, used her time to bridge the worlds of her Indigenous and European ancestry with the modern world in the context of her dark-sky work. She noted the importance in many Indigenous cultures of asking the question “How will people in seven generations live?” Howse also advised listeners to ponder that question in light of our activities that impact space and the night sky. It reminded attendees that the next frontier of dark-sky conservation involves social and environmental justice concerns. Diane Turnshek (Carnegie Mellon University) raised the issue of the increasing number of people who have never seen the Milky Way. It is therefore challenging to communicate with them about starry skies when this is not something they have directly experienced. Waleska Valle (Adler Planetarium) spoke about her experience working with youth in Chicago to identify the ways in which light pollution impacts their communities. And Doug Sam (University of Oregon) used the International Dark Sky Park designation effort at Mesa Verde National Park as a case study to examine such efforts through the theoretical framework of decolonization. “When we designate future IDSPs, we must involve native peoples as a matter of justice," Sam explained. Leora Radetzky (DesignLights Consortium) shows off samples of low-color temperature white LED lights. As usual, the scientific presentations were all high-quality and stimulated lively discussion. The main takeaways from the posters and talks include:

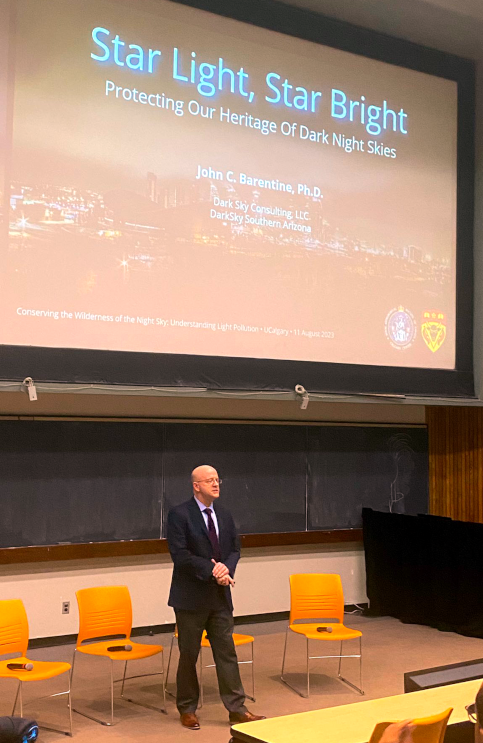

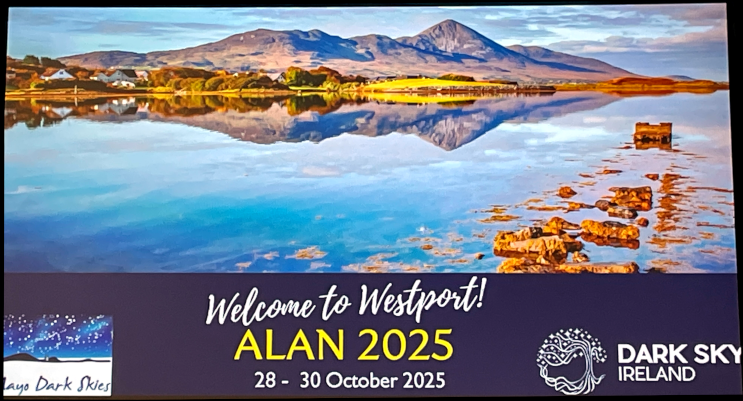

Friday night saw a successful public outreach event put on by the ALAN conference in coordination with the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Calgary Centre. About 300 people attended the event, which included an introductory talk about light pollution and a panel discussion with researchers. Afterward, attendees could view the night sky through telescopes set up on the University of Calgary campus. Dark Sky Consulting's John Barentine presents at the RASC Calgary Centre public event on Friday night. As participants began to disperse and head home beginning on Sunday, many reported how refreshing the experience was. ALAN 2013 was the first in-person conference in the series since 2018. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused the organizers to pivot to an online-only format. For many, the Calgary conference was the first time they saw their colleagues in person since 2019. Given that the research community is still small, the ALAN conferences feel more like village assemblies. A return to meaningful, in-person interactions supports the kind of collegiality that constantly draws students who want to make a career of night studies. It also supports collaborations that become friendships while yielding high-quality research results that push the field ahead. Announcement of the venue for the 2025 ALAN conference It is traditional to name the next host city at the conclusion of ALAN. On Sunday, attendees learned that the next meeting will be held in County Mayo, Republic of Ireland, in October 2025. Already many look forward to their next opportunity to present their work, reunite with old friends and meet new ones.

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

Credit: Virginia State Parks 923 words / 4 minute read The natural night sky looms large over humanity's past, present and future. Once a province only of the gods, the night sky is now our portal to understanding the universe. Light pollution, a phenomenon of only the last two centuries, now threatens to separate much of humanity from the starry heavens. Should access to a night sky unspoiled by light pollution be reserved only to those who live, or can travel to, rural places? Or should we aspire to a world that affords such access to all? Under one skyThere are many reasons why people work toward preserving dark night skies. As our window on the cosmos, the night sky is the source of information that fuels astronomy. "Astrotourists" travel around the world unique experiences under the stars. Closer to home, casual stargazers find recreation opportunities under almost any skies. We know that actions taken to protect the night sky have myriad benefits on the ground, too. Light pollution has negative effects on most wildlife species. Darker places, on the other hand, offer refuge to plants and animals already stressed by habitat loss and climate change. Better outdoor lighting can also improve public safety while using less energy. Taken altogether, these are powerful reasons for reducing light pollution. But if we set all that aside, there's an equally strong argument that access to the night sky has a prominent place in what it means to be human. Dark night skies were once accessible to all people in the world, and they inspired great works of art, literature and music. The sky is part of the cultural heritage of all humanity. It's one of the few aspects of the natural world that we all share. As such, it may be true that all people should have equal access to the stars. If so, then light pollution is more than an environmental threat. It interferes with access to an important cultural resource. Cheomseongdae, an astronomical observatory in Gyeongju, South Korea. Built in around the 7th century CE, it may be the oldest surviving such structure in the world. Photo by Flickr user ecodallaluna. An international viewTo date there is little recognition in law for these ideas. Many of the assertions about humanity's rights come from the United Nations. A few UN-sponsored activities have either implied a right to access the night sky or called for it outright. For example, Article 1 of the the La Laguna Declaration of 1994 asserts that “persons belonging to future generations have the right to an uncontaminated and undamaged Earth, including pure skies.” The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) held a conference on these ideas in 2007. The resulting "Declaration in Defense of the Night Sky and the Right to Starlight" considers "an unpolluted night sky" to be "an inalienable right of humankind". The Declaration elevates the right to starlight to a place alongside "all other environmental, social, and cultural rights". Another relevant UN statement is the 1972 UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. This action established the UNESCO World Heritage Programme. It has applied the label to astronomy sites, both ancient (e.g, the Chankillo Archaeoastronomical Complex, Peru) and modern (e.g., Jodrell Bank Observatory, UK). But so far it has resisted designating the night sky, or nighttime landscapes. The night sky is both cultural and natural heritage. It transcends national boundaries; there is, for instance, no "American sky" or "Chinese sky" belonging to those cultures alone. And it’s not a problem that the night sky, or space, is an “intangible” thing. UNESCO already recognizes such forms of cultural heritage. Under the existing framework, the night sky could receive the same kind of recognition and protection as any object the UN recognizes. The uses of outer space are now beginning to affect the quality of night skies on Earth. The space over our heads is increasingly crowded, with the planned launch of hundreds of thousands of new satellites in the 2020s. These satellite "megaconstellations" are gradually transforming the appearance of the night sky. And yet the main international treaty governing the use of space is silent on the subject. When the nations of the world signed the Outer Space Treaty in 1967, these concerns were on no one's radar. Photo by Warwick University Stars for all humankindThreats to human health from the pollution of air, water and soil can dictate measures to reduce those pollutants. There is an emerging consensus among researchers that nighttime darkness is key to our health and wellbeing. Reasons exist suggesting that regular access to nature is good for us. And there's even evidence of disparities in the way light at night affects poor neighborhoods and communities of color.

Does nature itself have some say in all this? Nations have begun to recognize certain "rights of nature" that can lead to rehabilitation of environmental harms. That's true even when no real person has suffered any obvious injury. Touted as a legal means to combat climate change, it's possible the same principles apply to night-sky conservation. In an era when so much divides us, whether neighbor versus neighbor of culture versus culture, the night sky is something we all share. Over time, we may come to realize that seeing the stars is not only something of value to people who can afford to escape the nighttime glow of the world's cities. Rather, it's an integral part of the human experience that should be available to all. Solving the global problem of light pollution is simple and cost effective. And it just might make all of our nights a little better. There are many ways to bring back the stars to the places where we live, work and play. Contact us today to find out how we can help.

Back to Blog

Credit: Flickr/dchrisoh 811 words / 3-minute read When you hear the phrase "dark skies", which thoughts and images come to mind? A night so dark that the stars are too many to count? The soft light of the Milky Way overhead? A sense of peace or serenity? Feelings of remoteness or isolation, wonder or awe? Maybe it's all of those things. The movement to protect the night sky from light pollution began in the 1970s. In those early days, it was firmly centered in the astronomy community. Even the name "dark skies" evokes astronomy and the cosmos. Organizations like the International Dark-Sky Association were born in reaction to the loss of the night. But the degradation of the night sky by human activities started far earlier. People noticed the stars disappearing soon after the introduction of gas lighting in the early 19th century. Astronomers began to leave cities and relocated their observatories to the countryside. The phenomenon ramped up quickly after 1900 due to the widespread introduction of electric lighting. Meanwhile, people began to notice that the situation was also beginning to change on the ground. Consider this observation published by the journal Science in 1887: "Some disadvantage or evil appears to be attendant upon every invention, and the electric light is not an exception in this respect. In this city they have been placed in positions with a view of illuminating the buildings, and a fine and striking effect is produced. At the same time, a species of spider has discovered that game is plentiful in their vicinity, and that he can ply his craft both day and night. In consequence, their webs are so thick and numerous that portions of the architectural ornamentation are no longer visible, and when torn down by the wind, or when they fall from decay, the refuse gives a dingy and dirty appearance to every thing it comes in contact with. It would be of interest to know whether this spider is confined to a certain latitude, and at what seasons of the year our temperature we can indulge in our illumination." Already people were beginning to see the effects of artificial light at night. Yet until very recently, we really didn't have a good understanding of how harmful those effects could be.

Today, we understand that the issue of light pollution is much more than about whether we can see the night sky. It touches on all these subjects:

At the same time, we shouldn't forget the allure of the stars. Early evidence suggests that 'astrotourism' is a growth industry that may see an explosion of interest as the Covid-19 pandemic eases. It can be an engine of economic development activity in rural areas, but only if skies there remain dark. And new concerns, like light pollution from satellites, continue to emerge. The diversity of effects caused by light pollution means there's something for everyone in the dark-skies movement. Some participants know little about astronomy but care deeply for better nighttime visibility. Concern for wildlife motivates others. And even those for whom breaking down barriers in society is a priority are coming to see lighting as an important consideration. Whether it's to see more stars, improve community safety at night or make conditions better for the ecology, pursuit of dark skies is key. Contact us today to find out how we can help achieve your goals. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed