Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

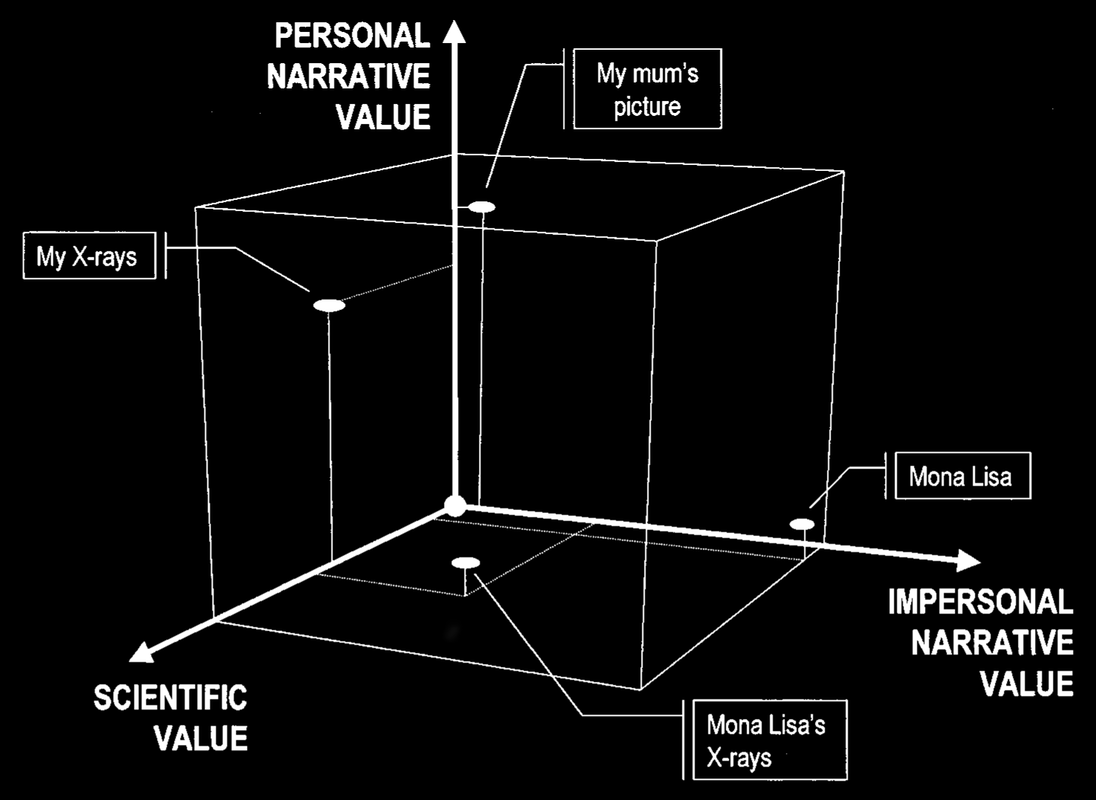

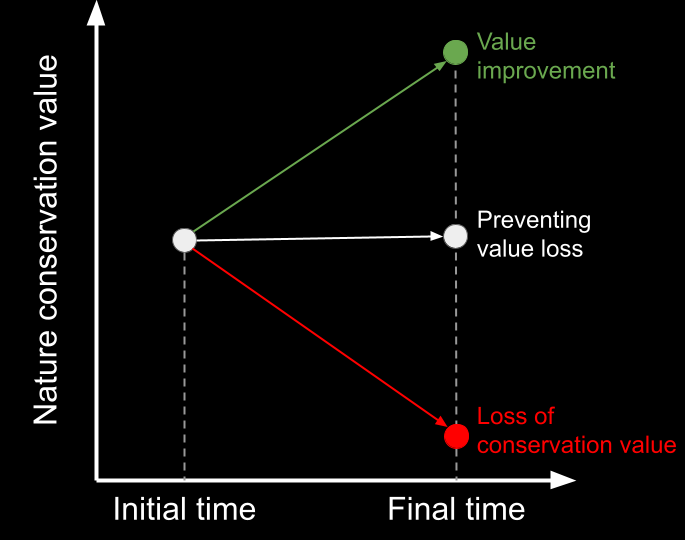

Image credit: Geoff Livingston 1150 words / 5-minute read When you hear the word "conservation", what comes to mind? Maybe turning off a running water tap, or upping the thermostat a little in summer. We take such actions for a variety of reasons, such as lowering bills and reducing our dependence on natural resources. But what motivates us to do these things in the first place? And how might it be different when the focus of conversation is something intangible? We sometimes encounter the idea of "conserving" dark night skies. The idea has been around at least since the early 1970s, taking the form of the protection of naturally dark places by astronomers. [1] At the start of the 21st century, the environmental conservation world began to take note. Now, at many parks and on protected lands, conservation professionals monitor the "quality" of night skies alongside the quality of air and water. Those professionals often refer to the "objects" of their conservation efforts. Air and water are easy to understand as "objects". But what about the beauty of a natural landscape or the historical significance of the ground? Can a dark night sky itself be a "conservation object"? Value and threatUnderstanding that requires a little background in conservation theory. Conservation related to "resources" which are usually natural in origin. Some resources are renewable, and some are not. Some renewable resources lose their renewability due to human interactions. Humans consider something a resource because they assign some kind of value to it. Resources become objects of conservation when one or more influences threaten their integrity. The combination of value + threat makes the "object" a target for conservation to ensure it continues to exist. In naming the conservation object here, we should consider the value and the threat. It also pays to think about the problem more broadly: the resource is best described as "nighttime darkness". A dark sky is a subset of that, because it's only half the landscape. The other half is the ground, where most concerns about harm to biology (including humans) exist. Nighttime darkness has value along several dimensions. One model holds that objects fall into a space defined by value to individuals, value to groups, and scientific value. [2] The farther an object is from the origin of this space, the more likely it is to be considered a conservation object. (Figure adapted from [2].) People clearly find value in nighttime darkness. For example, dark night skies have inspired humans to create great works of art. Some people report meaningful psychological and/or religious feelings when accessing dark skies. And there is evidence that regular exposure to nighttime darkness supports a sense of wellbeing and better health outcomes. At the same time, dark nights have an "impersonal" value at a level higher than the individual. The relationship between natural darkness and humans is a kind of intangible cultural heritage. It also relates to the welfare of wildlife and ecosystems that depend on it. And as "reservoirs" of darkness, naturally dark places are important laboratories for scientific studies. Some sciences like astronomy are dependent on access to them. The threat to this object of value is artificial light at night. It's not new; for at least 2,000 years people have observed the effects of light at night on plants and animals. The significance of that harm increased with the introduction of electric light about 140 years ago. And an understanding of how it affects people has matured only in about the past half-century. The threat to nighttime darkness materializes in the form of light pollution, which now affects much of the world. [3,4] From theory to practiceThis may all seem like an academic exercise. But there is a practical benefit to the kind of analysis that identifies natural darkness as a conservation object. Various bodies of knowledge, from environmental science to philosophy and ethics, help inform how to conserve it. The experience of practitioners over several decades shows us the best practices. And environmental history shows how framing the nature of the object leads to the most effective forms of advocacy and activism to protect it. The trajectory of a conservation approach can go one of three ways: it can improve the value of the object; "hold the line" in its current state; or see the degradation of the object leading to a loss of value. How it evolves in depends on the severity of the threat; how the nature of the threat changes over time; and how the perceived value of the object responds to the threat. Rarely is all this determined in advance. Rather, conservation is an open system that interacts with the world in complex ways. (Adapted from Figure 2 in [5].) Lastly, what does this teach us about protecting the things we care about? Conservation of a resource involves a certain kind of "value proposition". It asks the question: why should people care? People and groups who have been deprived of natural darkness, often for generations, might not find value in the resource. They might decide that conservation efforts are too difficult, and the rewards of success too far away in the future to matter today. In short, they might decide that the perceived risks outweigh the supposed benefits. How can we change this? To increase the value proposition, we must show clear benefits resulting from the behavioral changes needed to achieve conservation of the object. That may be the positive impacts of astrotourism on stagnant rural economies. Or it may be improved ecosystem resilience in the face of global climate change. People may come to see access to nighttime darkness as a factor that improves their quality of life. It could even be as simple as a desire to leave the world in better condition for the benefit of the generations that follow us. The path to protectionWhen people come to see the value proposition of conserving nighttime darkness, they are more likely to support the changes that will achieve its goals. Often these behavioral "nudges" are small, reducing the sense of investment in what may be seen as an uncertain outcome. Yet, unlike in the case of other forms of environmental pollution, improvement of the resource is immediate following actions taken to reduce light pollution. Seeing immediate results can help sustain and further conservation efforts once conditions begin to improve. The adoption of nighttime darkness conservation by environmental professionals is an important milestone along the road to saving dark night skies for our children and grandchildren. Achieving that goal involved elevating the resource to a high state of value and identifying a clear threat to its long-term stability. From there, the tools of the conservation trade can be adapted to protect it. Many groups are now considering how they can write these ideas into their plans and actions. We can help articulate the value proposition to stakeholders and devise strategies for dark-sky protection suitable for any size business or organization. Contact us today to find out more. References

0 Comments

Read More

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed